Commentary: Securing the Peace between Eritrea and Ethiopia

Part 1: Published 10 April 2018

(Part 1: PDF version)

The recent assertion of the new prime minister of Ethiopia, Dr. Abiy Ahmed, of his readiness to engage in peace talks to resolve the “no peace, no war” situation and normalise bilateral relations with Eritrea has drawn renewed international attention on the frozen conflict and spurred a flurry of discussions in the social media. Furthermore, it has rekindled fresh diplomatic initiatives to explore and widen a possible window of opportunity, encourage the parties to reengage, and facilitate a resolution of the Ethio-Eritrean conflict. This commentary, essentially a reproduction of Chapter 17: Securing the Peace between Eritrea and Ethiopia of Ambassador Andebrhan Welde Giorgis’ book, Eritrea at a Crossroads: A Narrative of Triumph, Betrayal and Hope (link), seeks to enrich the ongoing discussion, shed light on the underlying cause of the war and the stalled peace process, and contribute to a durable resolution of the unfinished boundary conflict as a crucial step towards the normalisation of bilateral relations.

Eri-Platform serialises the book’s Chapter 17 in four successive weekly parts: 1. General Introduction; 2. The Delimitation of the Boundary; 3. Virtual Demarcation of the Boundary; and 4. Imperative of Durable Peace. In order to put the still pending boundary conflict in context, the expanded General Introduction presents a brief overview of the boundary issue in Africa; a general background of the Ethio-Eritrean boundary dispute; and includes the Chapter’s original Introductory Remarks on the two peace agreements that brought the war to an end but have, to date, failed to secure the peace between Eritrea and Ethiopia.

- General Introduction

The state system and the associated notion of a delimited, stable and internationally recognised boundary in contemporary Africa are essentially a product of the European partition, conquest and colonisation of the continent. So are Eritrea and Ethiopia in their modern geopolitical formations and the international boundary separating them. The colonial system carved up new territorial entities that shaped the present political configuration of Africa.

The Organisation of African Unity (OAU) Charter (1963) adopted, the First OAU Summit of Heads of State and Government (1964) resolved, and the African Union (AU) Constitutive Act (2002) upheld, the principle of uti possidetis juris, the sanctity of colonial borders inherited at the attainment of independence among the independent states of Africa. In deciding to maintain the colonial borders, the Charter, the Summit and the Constitutive Act enshrined territorial integrity within the colonial border as a cardinal principle of the organised community of African states. The three landmarks of the premier pan-African organisation underlie the basic consideration that “border problems constitute a grave and permanent factor of dissention”, that “the borders of African States, on the day of their independence, constitute a tangible reality”, and that Member States “respect the borders existing on their achievement of national independence” (Resolution AHG/Res. 16(1) on Border Dispute among African States, Cairo, July 1964).

Eritrea and Ethiopia, like most contemporary states in Africa, owe their constructions, present geopolitical formations and respective international boundaries to imperial division, conquest and partition of territory in Africa. The international boundary between Eritrea and Ethiopia was delineated by three treaties signed between Italy and Ethiopia in 1900, between Italy, Ethiopia and Great Britain in 1902 and between Italy, Ethiopia and France in 1908. The three colonial treaties define the entire 1,000 Km-long Eritrea-Ethiopia boundary making use of explicit natural and geometric limitations, marking it as one of the most clearly defined boundaries anywhere in Africa. Delimited by these colonial treaties, Eritrea became, respectively, an Italian colony (1890-1941), an occupied enemy territory under British military administration (1941-52), federated with Ethiopia (1952-1962), and annexed by Ethiopia (1962-1991).

Eritrea retained the structure of its territory and the configuration of its boundary as defined by the three colonial treaties. The boundary retained formal international status during the periods of Italian colonial rule, British military occupation and federation with Ethiopia while it became a stable internal border during the period of Ethiopian annexation in 1962 and Eritrea’s liberation in 1991. Eritrea gained de facto independence in 1991 and de jure independence in 1993. The colonially delimited boundary between Eritrea and Ethiopia remained fixed, stable and locally as well as internationally recognised until four more years after the formal independence of Eritrea in 1993. It had remained remarkably stable in all three treaty sectors of the common border from the signing of the colonial treaties until Ethiopia’s issuance of a new map in 1997 unilaterally redrawing the common international border.

The 1900 treaty delimits the central sector of the boundary by tracing it along the Mereb, Belesa, and Muna rivers, continues beyond the junction of the Muna and Endeli rivers at Massolae onwards to Rendacoma, veering slightly southeast to the Salt Lake. The 1902 treaty delimits the western sector of the boundary by tracing it from the confluence of the Mereb and Mai Ambessa rivers along a south-westerly line to the junction between the Setit and Mai Tenné rivers (the point where the borders of Eritrea and the former Ethiopian provinces of Tigray and Begemdir meet), leaving Mount Ala Takura and all the Kunama lands within Eritrea; from there, the boundary continues along the Setit River to its confluence with the Khor Om Hajer at the point where the borders of Eritrea, Ethiopia and the Sudan meet. The 1908 treaty delimits the eastern sector of the boundary by tracing it from Rendacoma at a distance of 60 Km parallel to the Red Sea coast in a south-easterly direction all the way to Mount Mussa Ali at the point where the borders of Eritrea, Ethiopia and Djibouti meet (Welde Giorgis, 2014, 570-582).

Thus delimited, the international frontier separating Eritrea and Ethiopia held unchanged for nearly an entire century. Indeed, the historical colonial treaty border between the two countries had remained remarkably stable until Ethiopia’s unilateral redrawing of the boundary in 1997, whence it became a subject of precipitous interstate dispute. Otherwise, Eritrea had retained the integral structure of its territory and the configuration of its boundary as defined by the colonial treaties. This boundary enjoyed formal international status, both de jure and de facto, during the periods of Eritrea’s Italian colonial rule, British military occupation, and federation with Ethiopia. Even when it became de facto an internal border during the period between Ethiopian annexation in 1962 and Eritrean liberation in 1991, it retained its de jure international status.

The stable international status of the border, as established by the three colonial treaties during the European scramble for Africa, was sanctioned by the UN Federal Resolution 390 (1950) and Eritrea’s declaration of sovereign independence (1993). Formal Ethiopian contestation of the boundary happened only after the independence of Eritrea (Welde Giorgis, 2014, 510-512). Hence, the boundary conflict between Eritrea and Ethiopia, apart from that of South Sudan and Sudan, is quite unique of its kind in Africa in that it arises from state succession. The de facto dissolution of the Ethiopian Empire State in 1991 resulted in the separation of Eritrea and Ethiopia and Eritrea’s subsequent formal accession to de jure independence in 1993.

![[:swvar:text:838:]](/swfiles/files/tigray-manifest-1976.png?nc=1562756366)

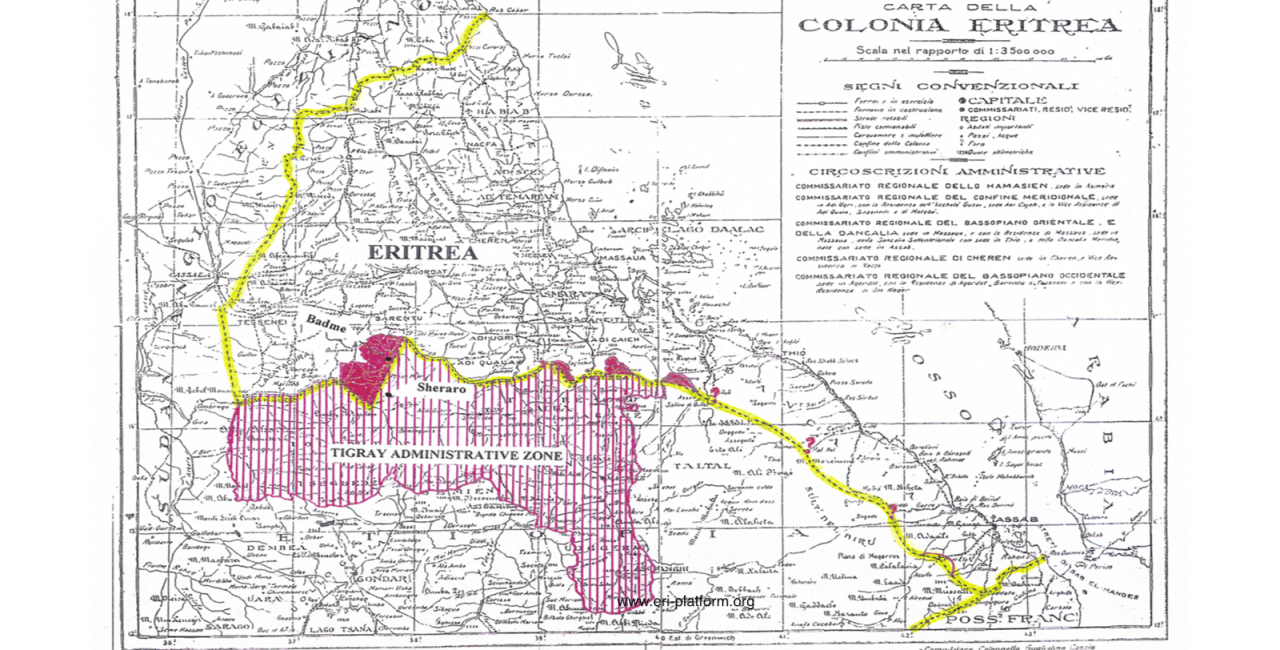

The genesis of the boundary conflict between Eritrea and Ethiopia lies in the Tigray People's Liberation Front's (TPLF) Manifesto 1976 whose declared final objective is secession from Ethiopia and the establishment of an independent Republic of Tigray that incorporates large swathes of territory from adjacent regions of Ethiopia and Eritrea. Accordingly, the administrative reorganisation of Ethiopia into a Federal Democratic Republic of regional states based on ethnic and/or linguistic factors in 1995 resulted in a significant enlargement of Tigray. Furthermore, Ethiopia issued an official map of Tigray Regional State in 1997, subsequently embossed in its new currency notes, incorporating large chunks of Eritrean territory in all three treaty sectors (click here for more info). The unilateral redrawing of the common border constituted a clear transgression of the colonial treaty boundary and a flagrant violation of Eritrea’s sovereignty and territorial integrity.

In July and August 1997, Ethiopia went beyond laying claims on paper to forcible occupation of hitherto uncontested Eritrean territories in the Bada and Badme areas, dismantling local Eritrean administration, and dispossessing and evicting Eritreans from the newly occupied localities. All this, in effect, constituted a declaration of war. Yet, the Government of Eritrea failed not only to defend the integrity of the national territory and protect the people but also to lodge either a formal protest or a diplomatic demarche, thereby missing opportunities to peacefully resolve the new contestation and avoid an unnecessary war (see Chapter 15: An Avoidable War in 'Eritrea at a Crossroads'). Furthermore, the government turned a deaf ear to the pleas and petitions for protection of the evicted populations and kept the Eritrean people at large, the Central Council of the ruling People’s Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ), the cabinet of ministers, the ambassadors, and the Eritrean National Assembly in the dark concerning the trouble brewing in the borderlands.

![Map 1: Tigray region before expansion. [:swvar:text:838:]](/swfiles/files/northern-ethiopia-until-1988.png?nc=1562756366)

![Map 2: Tigray region after expansion. [:swvar:text:838:]](/swfiles/files/tigray-after-1991-map.png?nc=1562756366)

![Map 3: Tigray expansion into Eritrea [:swvar:text:838:]](/swfiles/files/eritrea-ethiopia-full-map-view-border.png?nc=1562756366)

Eighteen years after the formal end of hostilities, sixteen years after the arbitral delimitation of the boundary, and twelve years after the virtual demarcation of the boundary, there appear to be two ways forward. The first would be a return to the status quo ante of 1993, the time of Eritrea’s achievement of national independence, in line with the principle of uti possidetis juris enshrined in the Charter of the OAU, the resolution of the First OAU Summit, and the Constitutive Act of the AU. This way forward would respect the historical colonial treaty border in adherence to the treaties and in consultation with the local population in the borderlands regarding the actual location of the boundary and restore the fraternal relations across a soft border. The second path forward would be to implement the Algiers Agreements between Eritrea and Ethiopia without further delay.

The following section is the Introductory Remarks reproduced from Chapter 17 which recounts the attempt to implement the Algiers Agreements.

_______________________________

Chapter 17: Securing the Peace between Eritrea and Ethiopia

War is the decision to go for victory [rather] than resolution. Peacemaking is an attempt to resolve the sources of the conflict and restore a situation of balance, thereby eliminating the need for victory and defeat. - Jim Wallis

The Peace Agreement of 12 December 2000 was the continuation of the Agreement on Cessation of Hostilities of 18 June 2000. This chapter notes the key provisions of the Algiers Agreements, summarises the final damage awards by the Claims Commission, and illustrates the territorial significance of the delimitation decision of the Boundary Commission. It highlights the efforts of the Boundary Commission to demarcate the boundary on the basis of the delimitation decision, appraises the respect or defiance of the Eritrean and Ethiopian governments of their obligations under the peace treaty, and describes the virtual demarcation of the boundary. It also assesses the role of the guarantors and witnesses of the Algiers accords in fulfilling or failing to meet their commitments under the agreements.

The objective here is not to put blame or to heap praise on any party. Rather, it is to portray the salient events as they happened and consider concrete positions as they unfolded in terms of the actions, or failures to act, of the concerned parties with a view to pointing the way forward to the resolution of this seemingly intractable problem.

The comprehensive peace accord reinforced the Agreement on Cessation of Hostilities and laid a framework for a lasting solution to the boundary issue and the restoration of durable peace and normal relations between Ethiopia and Eritrea. It provided for the permanent termination of hostilities between the two countries and the renunciation of the threat or use of force against each other. It stipulated the immediate release and repatriation of all prisoners of war (POWs) and other persons detained because of the war as well as the humane treatment of each other’s nationals and persons of each other’s national origin within their respective territories. In addition, the accord committed the two states to the peaceful settlement of disputes and respect for each other’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. Further, it provided for the establishment of three impartial and independent commissions, namely, an enquiry commission, a boundary commission and a claims commission.

Article 3 of the Agreement mandated the Enquiry Commission to conduct an investigation on the incidents of 6 May 1998 and the incidents of July and August 1997 in order to determine the origins of the conflict. It provided for the appointment of the Commission by the Secretary General of the OAU, in consultation with the Secretary General of the UN and the two parties. The Commission was required to “submit its report to the Secretary General of the OAU in a timely fashion”. However, no Enquiry Commission was established, no attempt made to conduct an investigation on the incidents of July and August 1997 and May 1998 and, therefore, no determination rendered of the origins of the conflict. The omission represented the first violation of the comprehensive peace agreement prejudicial to Eritrea’s case.

Article 4 of the Agreement mandated the Boundary Commission to delimit and demarcate the colonial treaty border based on the colonial treaties of 1900, 1902, and 1908 and applicable international law. It expressly denied the Commission the power to make decisions ex aequo et bono. It provided for the establishment of the Boundary Commission by the parties, seated in The Hague under the auspices of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and the UN Cartographer to serve as the Secretary of the Commission. In addition, it stipulated that the Commission start work within fifteen days after its constitution and decide the delimitation of the border within six months of its first meeting.

Further, the agreement committed the two governments to respect the inviolability of the colonial borders inherited at independence, as sanctioned by the OAU resolution adopted in the 1964 Cairo Summit. Most crucially, the parties agreed the decision of the Boundary Commission to be final and binding, to accept the border so determined, and to respect each other’s territorial integrity and sovereignty. They also agreed to fully cooperate with the Commission and facilitate its work during the process of delimitation and demarcation. On their part, the UN and the OAU pledged, as per the Agreement on Cessation of Hostilities, to guarantee the respect of the parties to their commitments under the agreement. In addition, the agreement provided for the UN to facilitate, upon request by the parties, resolution of issues that may arise due to the transfer of territorial control because of the delimitation and demarcation process.

Article 5 of the Agreement mandated the Claims Commission to decide, through binding arbitration, all reciprocal claims for loss, damage or injury by the two governments and their nationals, whether natural or juridical persons, against the other resulting from violations of international humanitarian law in connection with the border conflict. The mandate excluded consideration of claims arising from actual military operations or use of force. Like the decision of the Boundary Commission, the decisions and awards of the Claims Commission would be final and binding (as res judicata). Again, like the Boundary Commission, the Claims Commission lacked the power to make decisions ex aequo et bono. Fulfilment of the decisions and awards of the Commission aimed to help Eritrea and Ethiopia address the negative socioeconomic effects of the conflict on the civilian population, including deportees.

Unlike the Enquiry Commission, which never saw the light of day, the Boundary Commission and the Claims Commission were, duly established under the auspices of the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCJ) seated in The Hague. The PCJ served as a base and as a registry for the two commissions.[1] Both commissions fulfilled their mandate and disbanded.

The Eritrea-Ethiopia Claims Commission (EECC) conducted extensive briefings and hearings, examined the claims of each party against the other, and ruled on the merits of the rival claims. Eritrea and Ethiopia filed an enormous variety of claims for compensation in damages related to the war. In addressing these claims, the Eritrea- Ethiopia Claims Commission considered several categories of issues. Such issues included the lawfulness of the initial resort to force, the treatment of prisoners of war and civilian internees, the legality of means and methods of warfare used in various localities, the treatment of diplomatic premises and personnel, the seizure and destruction of private property, and the treatment by each side of the nationals of the other.

The Claims Commission rendered its decision on fifteen partial and final awards on liability between 1 July 2003 and 19 December 2005 and its decision on the final damage awards for the global losses suffered in the war on 17 August 2009. While Eritrea and Ethiopia filed claims for about US$6 billion and US$14.3 billion, respectively, the EECC awarded Ethiopia a total of US$174,036,520 and Eritrea a total of US$163,520,865, including $2,065,865 to individual Eritreans.[2] Although awarded US$10,515,655 more than Eritrea, Ethiopia expressed dismay at the amount of its assessed compensation in light of the Commission’s earlier rulings on relative liability while Eritrea accepted the decision without complaint. In concluding its decision on the two Final Awards, the Claims Commission expressed confidence that Eritrea and Ethiopia “will ensure that the compensation awarded will be paid promptly, and that funds received in respect of their claims will be used to provide relief to their civilian populations injured in the war”.[3]

Part 2 will deal with the Eritrea-Ethiopia Boundary Commission’s Delimitation Decision…

Endnotes for Part 1:

[1] The Boundary Commission consisted of Bola Ajibola, Elihu Lauterpacht (the President), Michael Reisman, Stephen Schwebel and Arthur Watts; the Claims Commission consisted of George Aldrich, John Crook, Hans van Houette (the President), James Paul and Lucy Reed.

[2] Eritrea-Ethiopia Claims Commission Final Award: Eritrea’s Damages Claims and Ethiopia’s Damages Claims between The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia and The State of Eritrea, The Hague, 17 August 2009.

[3] Final Award: Eritrea’s Damages Claims, (Erit.-Eth.), at § IX (Aug. 17, 2009); Final Award: Ethiopia’s Damages Claims, (Erit.-Eth.), at § XII (Aug. 17, 2009).

Eri-Platform serialises the book’s Chapter 17 in four successive weekly parts: 1. General Introduction (released 10.04.2018); 2. The Delimitation of the Boundary (released 16.04.2018); 3. Virtual Demarcation of the Boundary; and 4. Imperative of Durable Peace.

Part 1 General Introduction presented a brief overview of the boundary issue in Africa and the boundary conflict between Eritrea and Ethiopia and introduced the Algiers Treaty comprising the Agreement on Cessation of Hostilities (18 June 2000) and the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (12 December 2000) whose expeditious implementation aimed to secure the peace between Eritrea and Ethiopia. Part 2 The Delimitation of the Boundary follows.

The following section is the second serialisation of Chapter 17 which recounts the attempt to implement the Algiers Agreements.

________________________

[continued…]

17.1 The Delimitation of the Boundary

The Eritrea-Ethiopia Boundary Commission (EEBC), fully constituted on 20 February 2001, immediately set out to “delimit and demarcate” the Ethiopia-Eritrea border. It approached the delimitation of the boundary in the Western, Central, and Eastern sectors corresponding to three colonial treaties. It received and studied written submissions and oral arguments of treaty border claims by Eritrea and Ethiopia. After examining the merits of the territorial claims of each Party based on the colonial treaties of 1900, 1902, and 1908 and applicable international law, the EEBC delivered its Delimitation Decision on 13 April 2002. The Decision defined the salient features of the boundary line and identified the key coordinates connecting it.

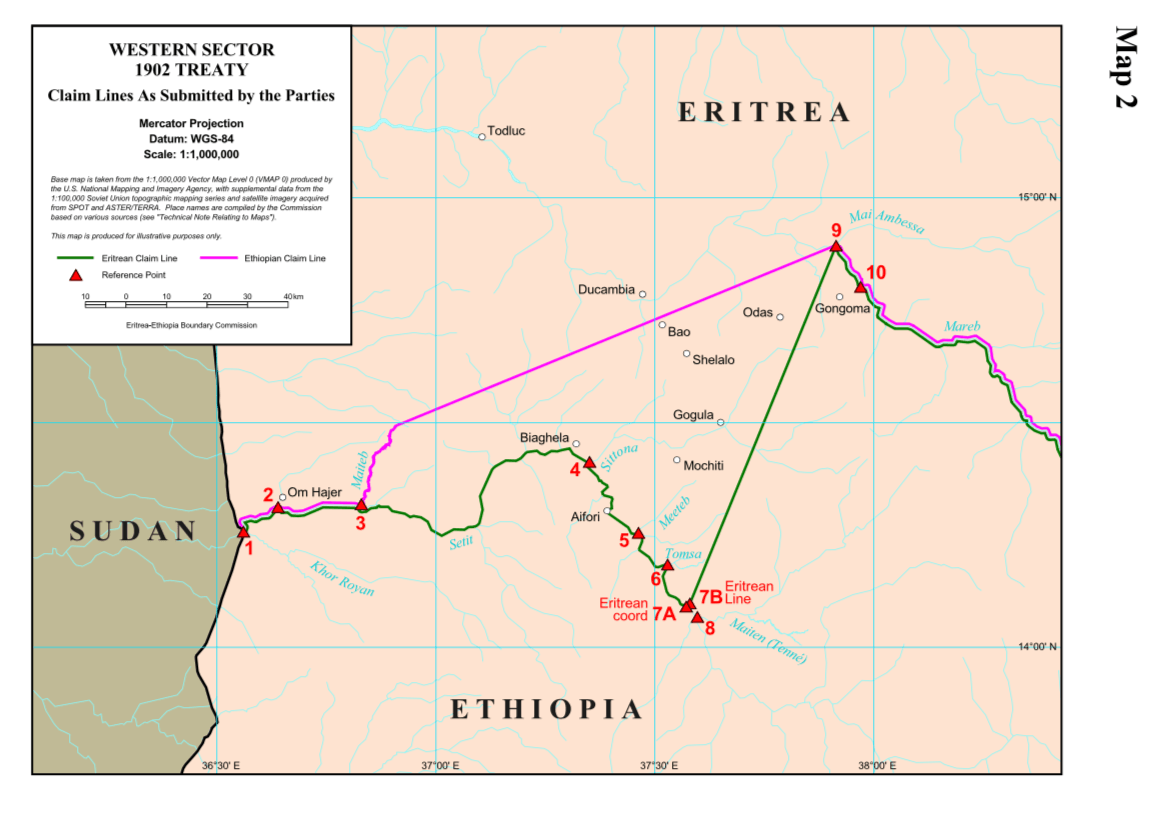

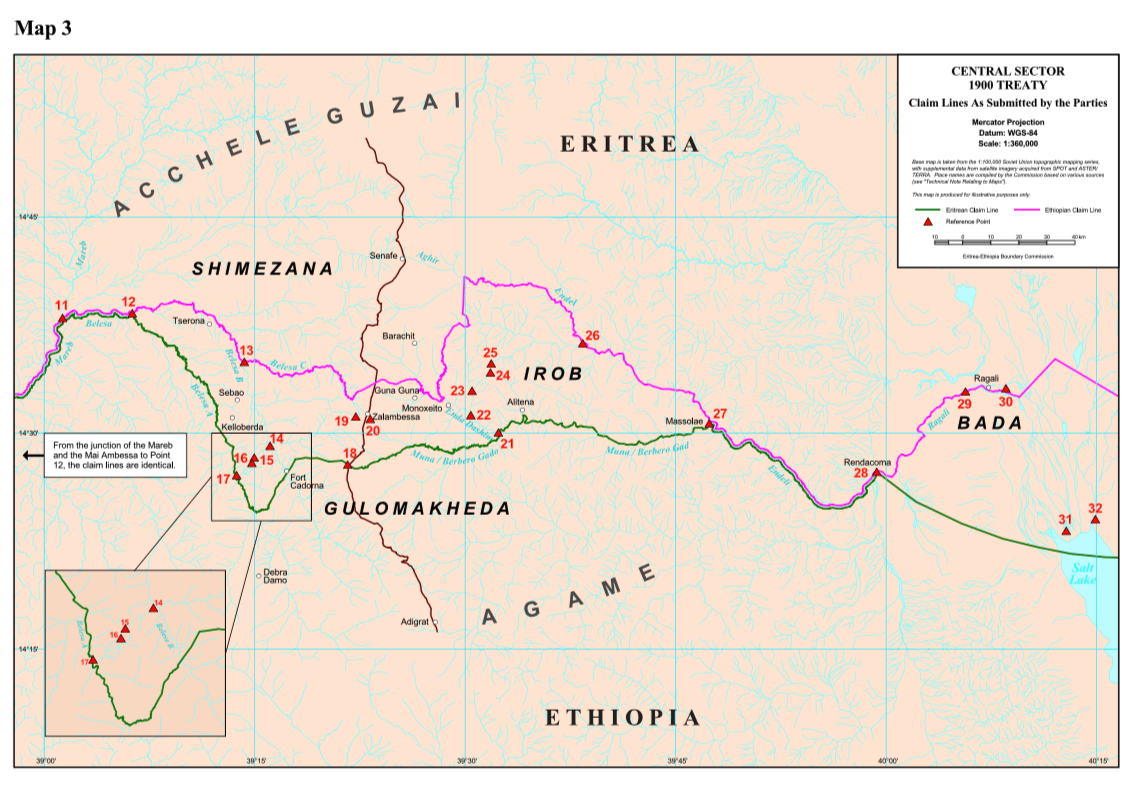

Map 3 shows the 1902 Treaty Claim Lines of Ethiopia

and Eritrea in the Mereb-Setit section of the Western Sector of the

Eritrea-Ethiopia boundary. The Ethiopian claim line stretched from the

confluence of the Mereb and Mai Ambessa rivers (Point 9) in the northeast to

the confluence of the Setit and Maiteb rivers (Point 3) in the southwest.

Eritrea initially argued that a straight line connecting the confluence of the

Mereb and Mai Ambessa rivers (Point 9) in the northeast to the confluence of

the Setit and Maiten (Mai Tenné) rivers (Point 8) in the southwest delineated

the colonial treaty border. Later, it submitted that the established boundary

line ran from the confluence of the Mereb and Mai Ambessa rivers (Point 9) to the

confluence of the Setit and Tomsa rivers (Point 6). Moreover, in its final

submissions, Eritrea gave two different locations (7A and 7B) as the southern

terminus of the straight line connecting to the confluence of the Mereb and Mai

Ambessa rivers (Point 9). It also suggested that the original Treaty reference

was actually to the confluence of the Setit and Sittona rivers (Point 4)

linking to Point 9.[1]

![Map 3: The Ethiopian and Eritrean Claim Lines in the Western Sector (EEBC Map 2) [:swvar:text:838:]](/swfiles/files/map-3-preview.png?nc=1562756366)

The Boundary Commission examined the Ethiopian and Eritrean Claim Lines against the evidence. Its interpretation of the 1902 Treaty between Britain, Ethiopia and Italy established the Eritrea-Ethiopia boundary in the Mereb-Setit section of the Western Sector as a straight line connecting the confluence of the Mereb and Mai Ambessa rivers in the northeast (Point 9) with the confluence of the Setit and Maiten (Mai Tenné) rivers in the southwest (Point 8).[2] This straight line leaves Mount Tacura and the Cunama [Kunama] lands within Eritrea in accordance with the “Terms of the Treaty” as well as “The object and purpose of the Treaty”.[3]

Further, the Boundary Commission examined the rival claim lines in terms of applicable international law, considered in the context of “developments subsequent to the Treaty”.[4] It found that Ethiopia’s “claim to have exercised administrative authority west of the Eritrean claim line” lacked “evidence of administration of the area sufficiently clear in location, substantial in scope or extensive in time to displace the title of Eritrea that had crystallized as of 1935”.[5]

The Boundary Commission’s interpretation of the 1902 trilateral treaty and consideration of applicable international law upheld the historical colonial treaty border in the Western Sector. Eritrea had however, submitted variable Treaty Claim Lines corresponding to different locations of the southwestern terminus at the junction of several rivers with the Setit River. The EEBC used Eritrea’s inconsistency as a pretext to decide the straight line connecting the confluence of the Mereb and Mai Ambessa rivers (Point 9) with the confluence of the Setit and Tomsa Rivers (Point 6) as the international boundary in the Mereb-Setit section of the Western Sector. The submission of variable Treaty Claim Lines cost Eritrea the sliver of territory represented by the 9-6-8 triangle in Map 3, or the heavily shaded area in the Western Sector in Map 6.[6]

Map 4 shows the 1900 Treaty Claim Lines of Ethiopia and Eritrea in the Central Sector of the Eritrea-Ethiopia boundary. This sector extends from the confluence of the Mereb and Mai Ambessa rivers in the west along the Mereb-Belesa-Muna line, continues beyond the junction of the Muna and Endeli rivers at Massolae (Point 27) to Rendacoma (Point 28), and veers slightly southeast to the Salt Lake (Point 31) in the east.

Both Ethiopia

and Eritrea agreed on the description of the boundary line in the 1900 Treaty

as the “Mereb-Belesa- Muna” line, also depicted in a map annexed to the Treaty.

They also agreed on the Treaty description of the Belesa River stretch but

disputed the treaty location of its course. The task of the Commission in the

Central Sector was thus, reduced to identifying the courses of the Mereb,

Belesa, and Muna rivers as the delimitation line under the Treaty. Eritrea’s

claim line corresponded with the courses of the rivers as represented “on the

1894 map that formed the basis of the Treaty map”[7] and

subsequent maps of the historical colonial treaty border between the two

countries.

![Map 4: The Ethiopian and Eritrean Claim Lines in the Central Sector (EEBC Map 3) [:swvar:text:838:]](/swfiles/files/map-4-the-ethiopian-and-eritrean-claim-lines-in-the-central-sector-eebc-map-3.png?nc=1562756366)

As a bargaining chip, Ethiopia claimed title to large swathes of territory north of the 1900 Treaty border. It contended that the Commission’s task was not so much to interpret and apply the de jure geography of the Treaty’s Mereb-Belesa-Muna line as it was to determine the de facto administrative division between the Italian controlled Akele Guzai (Eritrea) and the Abyssinian controlled Agame (Tigray) districts at the time. It challenged the geographic accuracy of the depiction of the Belesa and Muna rivers on the 1900 Treaty map. Further, Ethiopia contested that, given variations in the local nomenclature for the rivers and their main branches, the Belesa and, in particular, the Muna describe relevant rivers in the region identifiable in 1900 as located on the 1900 Treaty map.[8]

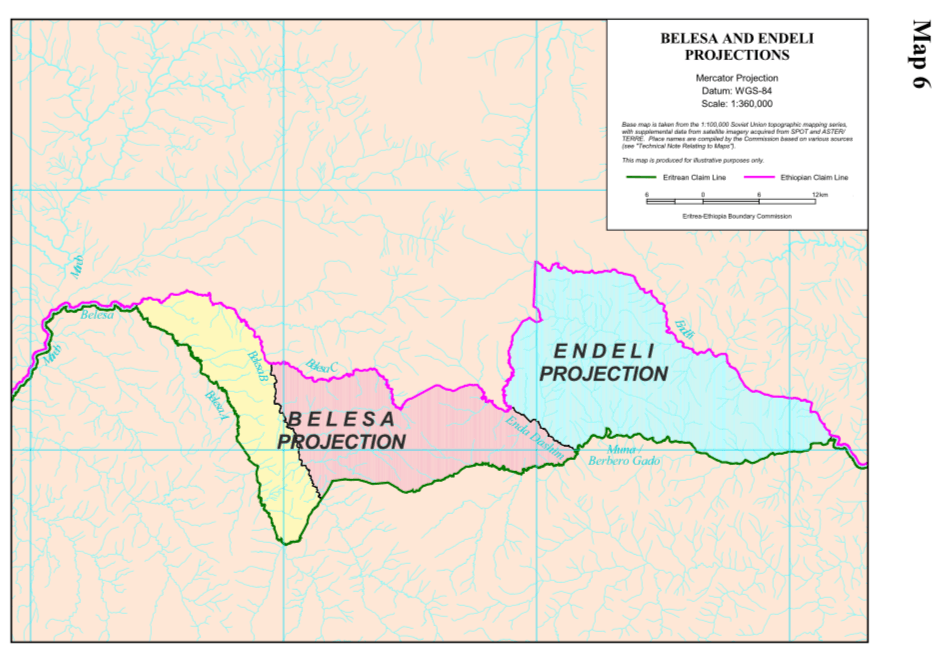

The Commission reviewed the rival claims over the identity of the Belesa and Muna rivers in the framework of what it labelled as the Belesa Projection and the Endeli Projection. In dealing with the Eritrean and Ethiopian contention regarding the identity of the course of the Belesa River in the Belesa Projection, the Commission ignored the substance of the treaty and the evidence of the map accompanying it. Instead, it resorted to an interpretation of the original intention of the parties to the 1900 Treaty, namely, Italy and Ethiopia, and the significance of the omission of the names of certain tributaries of the Belesa in the Treaty’s text in order to identify the “intended” Treaty course of the Belesa River.[9]

The subsequent interpretation of original “intent” led the Commission to conclude that the parties “intended” the Tserona River, a tributary of the Belesa River flowing from the northeast, as the Treaty location of the Belesa River and that the omission of the tributary’s name in the Treaty’s text was deliberate rather than an oversight or a mistake. Such a speculative conclusion left “Fort Cadorna, Monoxeito, Guna Guna, and Tserona”, localities that Ethiopia’s written submission described as “undisputed Eritrean places”,[10] on the Ethiopian side of the Treaty line.

Ethiopia’s claim of the Belesa Projection conflicted with its official admission that several localities within that area indisputably belong to Eritrea. This conflict calls into serious question the validity of the Commission’s interpretation that the course of the Tserona River was the intended Treaty location of the Belesa section of the Mereb-Belesa-Muna line. It is very difficult to imagine that grasp of such an anomalous speculation escaped the learned, intelligent, and honourable commissioners of the EEBC.

Having so determined the identity of the Belesa River, the Commission proceeded to delineate the overland link between the headwaters of the Belesa (Point 19) and Muna (Point 20) rivers as the Treaty line. In addressing the Ethio-Eritrean contention with respect to the identity of the Muna River, the Commission established the Muna/Berbero Gado-Endeli-Ragali course as the Treaty line in the Endeli Projection (Irob). Cumulatively, therefore, the Boundary Commission’s interpretation of the 1900 Treaty Line established the Eritrea-Ethiopia boundary in the Central Sector as the Mereb-Belesa (-Tserona)-Muna/Berbero Gado-Endeli-Ragali line continuing to its terminus at the Salt Lake in accordance with “The object and purpose of the Treaty”.[11]

In terms of applicable international law, considered in the context of “subsequent conduct”, the Commission addressed the claims of the Parties in relation to the exercise of sovereign authority in, the diplomatic record or official exchanges on, and maps of the Belesa Projection, the Endeli Projection, and the Bada region and made two qualifications:

1. It modified its contentious interpretation of the ‘intended’ Treaty line concerning the Belesa Projection to place the bulk of the eastern part of the Belesa Projection and the town of Tserona, the Akhran region, and Fort Cadorna in the western part of the Belesa Projection in Eritrean territory. It further modified the Treaty line in the eastern part of the Belesa Projection to place the town of Zalambesa in Ethiopian territory.

2. It revised the Muna/Berbero Gado section of the Treaty line to place the southerly and easterly parts of the Endeli Projection in Ethiopian territory.

Finally, the Commission maintained the Endeli-Ragali section of the Mereb-Belesa (-Tserona)-Muna/Berbero Gado-Endeli-Ragali line continuing to its terminus at the Salt Lake as the Treaty line, leaving Bada in Ethiopian territory.[12]

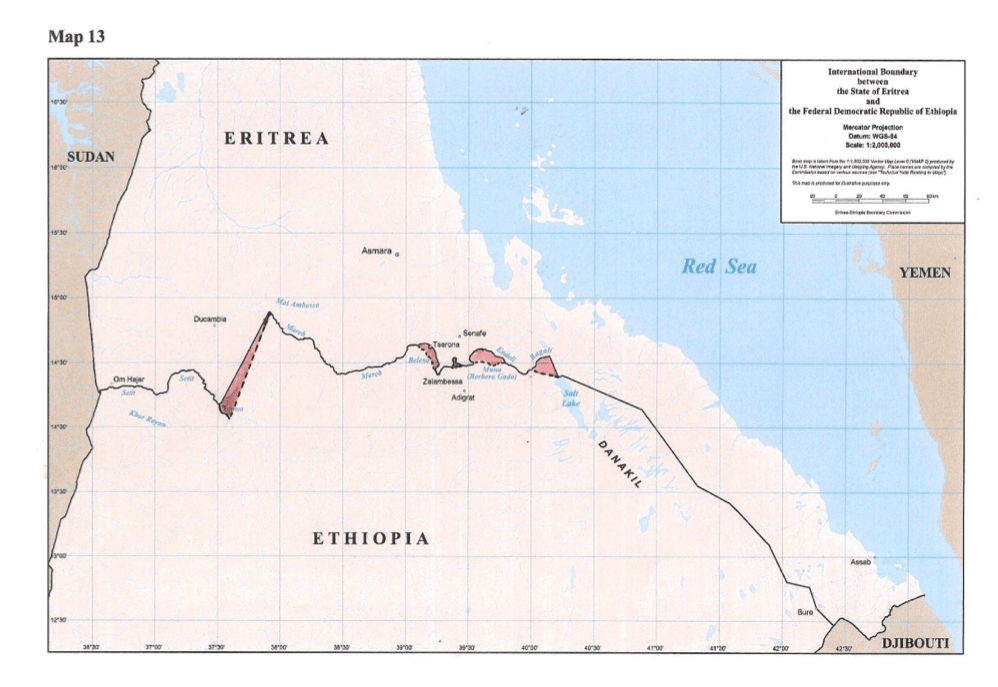

Map 6 shows the territorial consequence of the Boundary Commission’s modification of the 1900 Treaty line in the Central Sector for Eritrea and Ethiopia. The heavily shaded patches of territory in the western part of the Belesa Projection, around Zalambesa, in the eastern and southern parts of the Indeli Projection (Irob) and the Bada region, signify areas awarded to Ethiopia by the decision of the Eritrea-Ethiopia Boundary Commission.

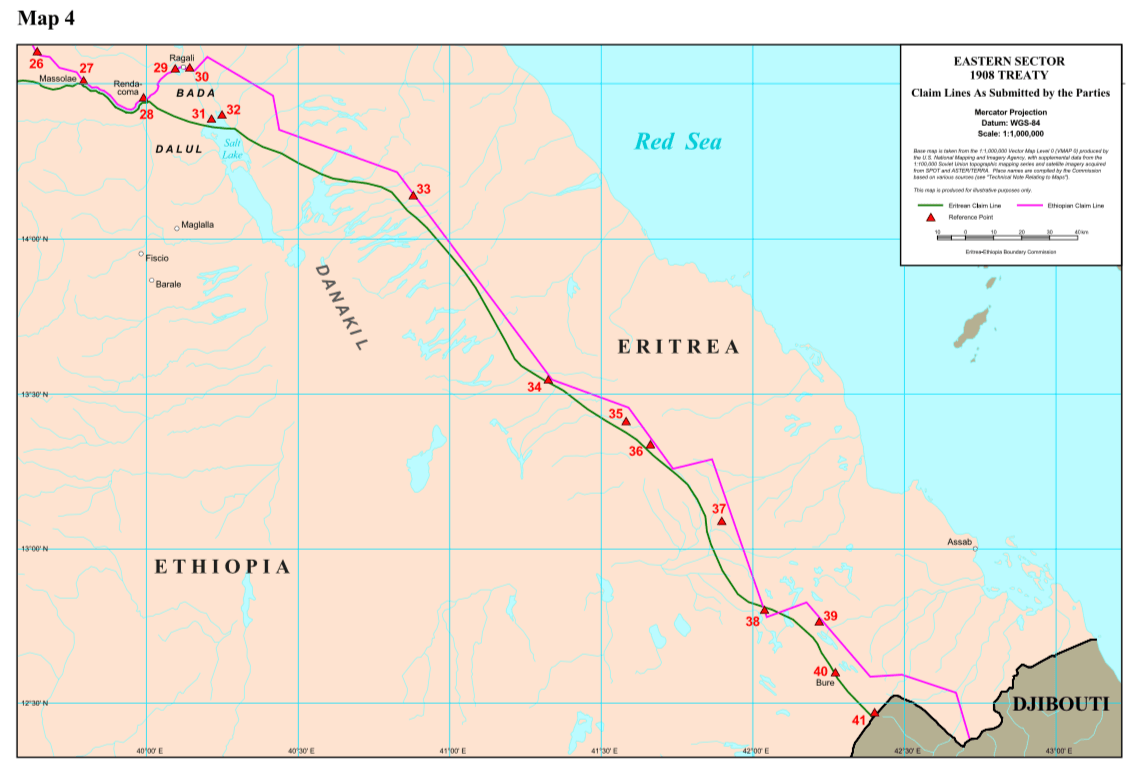

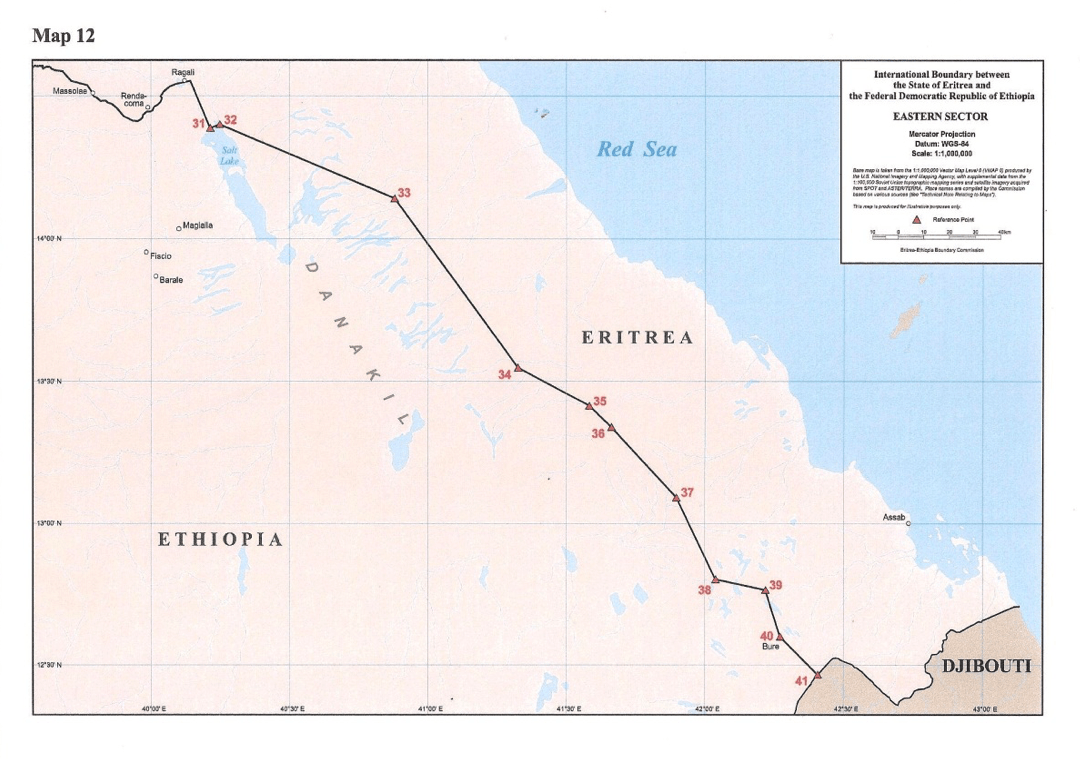

Map 5 shows the 1908 Treaty Claim Lines of Ethiopia and Eritrea in the Eastern Sector of the Eritrea-Ethiopia boundary. The dispute in this Sector centred mainly on the Bada area, Bure, and three technical issues. First, locating the starting point at the most westerly end; second, deciding the proper way of drawing the Treaty line running parallel to the coast at a distance of sixty kilometres inland; and third, determining the eastern terminus of the boundary or the trilateral junction of the border between Eritrea, Ethiopia and Djibouti.

![Map 5: Ethiopian and Eritrean Claim Lines in the Eastern Sector (EEBC Map 4) [:swvar:text:838:]](/swfiles/files/map-5-ethiopian-and-eritrean-claim-lines-in-the-eastern-sector-eebc-map-4-.png?nc=1562756366)

In establishing the eastern terminus of the Central Sector at Point 31 at the northern edge of the Salt Lake, rather than at Rendacoma (point 28), the Commission had already decided the western terminus of the Eastern Sector. The Commission first resolved the method of drawing the inland line running parallel to the coast and determined the location of the eastern terminus atop Mount Mussa Ali. It then essentially confirmed the Treaty line with the proviso that it passes at a point, lying equidistant between the Eritrean and Ethiopian checkpoints, at Bure (Point 40) to the border with Djibouti (Point 41), as shown in Map 5.[13]

![Map 6: New International Boundary between Eritrea and Ethiopia (the EEBC’s Map 13; shades inserted by the author) [:swvar:text:838:]](/swfiles/files/map-6-new-international-boundary-between-eritrea-and-ethiopia-the-eebcs-map-13-shades-inserted-by-the-author.png?nc=1562756366)

Map 6 shows the new international boundary between the State of Eritrea and the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, with the heavily shaded areas indicating the territorial effect of the delimitation decision of the Boundary Commission on the historical colonial treaty border. The decision of the Boundary Commission effectively modified the historical colonial treaty border between the two states in favour of Ethiopia. The map depicts that the delimitation decision of the Boundary Commission, as an arbitral determination of the boundary, essentially ceded to Ethiopia the red-shaded strips of land in the Western, Central, and Eastern sectors that the colonial treaties of 1900, 1902, and 1908 had placed in Eritrean territory.

Predictably, there was a marked contrast in the immediate public reaction of the two states to the eagerly awaited announcement of the Boundary Commission’s Delimitation Decision on 13 April 2002. In a swift response, the Ethiopian government declared victory and the state media in Addis Ababa exuded a celebratory mood. The Eritrean government issued no official statement on that notable day; the state media merely broke the news and, in a display of uncertainty as to the territorial significance of the ruling, the country’s television station kept on flashing the new delimitation line in the different sectors of the border without comment.

At the time, I was in Madrid, Spain, representing Eritrea at the Second World Assembly on Ageing. The event coincided with the beginning of my second tour of duty as ambassador to the EU and several EU Member States, including Spain. From my hotel room in Madrid, I called the Eritrean delegation that attended the Boundary Commission’s announcement ceremony in The Hague and asked for details of the Delimitation Decision. I also called the President’s Office in Asmera to get a feel of the official mood and find out what was happening and learned that the government was taking time to study the meaning of the Decision.

Impatient with the lack of a clear explanation, I requested Foreign Minister Ali Said Abdella, at the head the Eritrean delegation in The Hague, to send me a copy of the substantive decision. Ali faxed me the Dispositif (Chapter VIII) of the Decision and we discussed, over the phone, its attendant territorial implications for Eritrea vis-à-vis the historical colonial treaty border. We agreed on the obvious need to inform forthwith the Eritrean people at home and abroad, made the more anxious by an Eritrean silence in the face of an Ethiopian declaration of victory.

In a statement issued in the name of the council of ministers,[15] Ethiopia declared that the EEBC’s decision has restored all ‘forcibly seized Ethiopian territories’ in the three Treaty sectors to Ethiopia. It reiterated its respect for the Boundary Commission for performing its task with fidelity and a high sense of responsibility, and affirmed its acceptance of the ‘just and legitimate’ Decision and readiness to implement it in accordance with the Algiers Agreement. Further, it expressed its desire for the expeditious physical demarcation of the boundary, strongly urging Eritrea to honour its obligation to cooperate with the effort to demarcate the border.

Upon studying the EEBC Decision, Eritrea stated its acceptance and declared victory, despite the obvious loss of territory. Nevertheless, the unequivocal initial acceptance of the Delimitation Decision by both Parties augured well for the expeditious demarcation of the border on the ground and the successful completion of the peace process. The following section highlights the EEBC’s work to demarcate the boundary.

Part 3 will deal with the Virtual Demarcation of the Boundary …

Endnotes for Part 2:

[1] Eritrea-Ethiopia Boundary Commission, Decision, 13 April 2002, p. 60.

[2] Given the nominal role of the foreign minister, Eritrea’s chief counsel dealt with the president, directly or via Yemane Gebremeskel (Charlie) and Yemane Gebreab (Monkey). There was no involvement of available national expertise in preparing the case. Eritrea’s later submission of a correct treaty-line map prepared by the Commission for Coordination with UNMEE in collaboration with the competent government agencies came too late to undo, in the eyes of the Boundary Commission, the damage done by its previous incorrect submissions.

[3] Ibid., p. 61-69.

[4] Ibid., p. 69-84.

[5] Ibid., p. 84.

[6] Map 6 (EEBC 13), reproduced by the author in June 2002 for use in a series of seminars presented to Eritrean communities in the diaspora in Frankfurt on 15 June 2002, Stuttgart on 16 June 2002, Köln on 6 July 2002, Paris on 14 September 2002, Brussels on 21 September 2002, etc. The shaded areas indicate the territorial significance of the delimitation decision of the Boundary Commission and show the new international boundary vis-à-vis the historical colonial treaty border. The shades in red signify Eritrea’s loss, or Ethiopia’s gain, of territory arising from the Boundary Commission’s revision of the historical colonial treaty map of the boundary between the two states.

[7] Ibid., p. 18.

[8] Ibid., p. 19.

[9] Ibid., p. 31-38.

[10] Ibid., p. 50.

[11] Ibid., p. 45-48. For the Commission’s interpretation of the 1900 Treaty Line, see Map 7 on page 47.

[12] Ibid., p. 49-56.

[13] Ibid., p. 101.

[14] Eritrea-Ethiopia Boundary Commission, DECISION Regarding Delimitation of the Border between The State of Eritrea and the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, The Hague, 13 April 2002.

[15] ከሚንስትሮች ምክር ቤት የተሰጠ መግለጫ (author’s paraphrasing from the original Amharic), Walta Information Center -Amharic, 13 April 2002. http://www.waltainfo.com/Boundary/Ethio_Eritrea/ Boundary/Amharic.htm

Eri-Platform serialises the book’s Chapter 17 in four successive weekly parts: 1. General Introduction (released 10.04.2018); 2. The Delimitation of the Boundary (released 16.04.2018); 3. Virtual Demarcation of the Boundary (released 23.04.2018); and 4. Imperative of Durable Peace.

Part 3 The Virtual Demarcation of the Boundary follows.

The following section is the third serialisation of Chapter 17 which recounts the attempt to implement the Algiers Agreements.

_______________________________

[continued…]

17.2 The Virtual Demarcation of the Boundary

Article 4(13) of the Algiers Agreement required the “expeditious demarcation” of the boundary. Upon delivery of its Delimitation Decision, the EEBC set out to demarcate the boundary in consultation with and the cooperation of the Secretary General of the United Nations. Just as it did with the delimitation process, the Boundary Commission approached the task in three sectors based on the colonial treaties. It had, in anticipation of the emplacement of pillars as boundary markers along the delimitation line, already appointed a Chief Surveyor in October 2001 and established Field Offices in Addis Ababa and Asmera in November 2001. The Chief Surveyor, with a staff of assistant surveyors hired by the Commission, set up residence in Asmera on 15 November 2001. Furthermore, the EEBC appointed a Special Consultant to provide it with technical advice and assistance in May 2002 and established a third Field Office in Adigrat, northern Ethiopia, in July 2002.[1]

However, there were obstacles and ominous signs of contention on the horizon right from the start of the demarcation process. On 27 April 2002, Ethiopia forbade “further work within the territory under its control”, and interrupted the work of aerial photography and ground survey to construct a 1:25,000 map of the border to serve as a basis for demarcation.[2] Furthermore, a month after issuing its clear acceptance of the Delimitation Decision, Ethiopia submitted a long Request for Interpretation, Correction and Consultation regarding the Decision.[3]

Ethiopia filed a request for comments within the 30-day period allowed in the Commission’s Rules of Procedure. Eritrea characterised the Ethiopian request as an attempt at “a wholesale revision of the 13 April 2002 Decision” and called for its dismissal as “inadmissible under the Commission’s Rules of Procedure” and “inconsistent with the 12 December 2000 Algiers Peace Agreement”.[4] After due consideration of the Ethiopian request and the Eritrean submission in the context of its mandate, the Boundary Commission decided that, “the Ethiopian request is inadmissible and no further action will be taken upon it”.[5]

The Commission also received, and duly responded to, a letter from the President of Eritrea on 17 May 2002 raising, “rather unusually in relation to an arbitral proceeding” in its view, four questions regarding the basis used, the procedures followed or any political pressures exerted in reaching the Decision and whether the Decision was final and binding.[6] The Commission replied to the Eritrean President’s letter on 21 May 2002. The same day, it met with the Parties to discuss the modalities and technical aspects of the demarcation process, the role of the UN Mission in Eritrea and Ethiopia (UNMEE) and the Mine Action Coordinating Centre (MACC), and the establishment and role of field offices within Ethiopia. It also urged Ethiopia to resume cooperation immediately with the Boundary Commission in the demarcation process.[7]

Reminding it of its treaty obligation to cooperate without conditions, the Commission requested Ethiopia to allow the completion of the work before the start of the rainy season. Nevertheless, Ethiopia continued to prohibit fieldwork in the border areas under its control. Its refusal to lift the ban was followed by a letter, dated 15 May 2002, to the Boundary Commission from the Ethiopian foreign minister criticising UNMEE’s logistical assistance to the Chief Surveyor and casting doubt about the neutrality of the Boundary Commission’s Field Office”.[8]

Meanwhile, Eritrea accused Ethiopia of settling its nationals in Eritrean sovereign territory around Badme as of July 2002 and requested the Commission to instruct Ethiopia to undo the new settlements.[9] The Commission, acting on a report of the findings of a Field Investigation Team[10] sent to visit the places in question, ordered Ethiopia to dismantle its new settlements by “no later than 30 September 2002” and instructed each Party to ensure that “no further population settlement takes place across the delimitation line established by the Decision of 13 April 2002”.[11] When Ethiopia ignored the Order, the Commission reiterated that, “the Delimitation Decision of 13 April 2002 is final and binding in respect of the whole of the boundary between the Parties”. Further, it ruled that, “Ethiopia, in failing to remove from Eritrean territory persons of Ethiopian origin who have moved into that territory subsequent to the date of the Delimitation Decision, has not complied with its obligations.”[12]

In continuation of its preparatory steps and extensive consultation with the Parties, the Boundary Commission issued detailed Demarcation Directions on 8 July 2002, subsequently revised in November 2002 and in March and July 2003. The Demarcation Directions defined the objective of demarcation as the construction of ground pillars along the delimitation line. They indicated that the work of demarcation would be carried out through the Field Offices by the UN Cartographer, the Special Consultant of the Commission, the Chief Surveyor, and any other persons appointed for the purpose under the authority of the Commission. They also provided for each Party’s nomination of a high level Liaison Representative, Deputy Liaison Representative, and two Field Liaison Officers and required each Party to allow unrestricted freedom of movement for the demarcation personnel within its territory.

Further, the Demarcation Directions specified that the demarcation would take place on the basis of a “1:25,000 scale map”; that “pillar emplacements shall begin in the Eastern Sector, without prejudice to the continuance of preparatory steps for pillar emplacement in the Western and Central Sectors”; that the construction of the pillars “shall be done by contractors hired by the United Nations on behalf of the Commission”; and that “the Commission has no authority to vary the boundary line. If it runs through and divides a town or village, the line may be varied only on the basis of an express request agreed between and made by both parties”.[13]

Based on the Boundary Commission’s initial Schedule of Activities, revised on 19 February 2003, demarcation started in the Eastern Sector in March 2003. In a final revision of the Schedule of Activities on 16 July 2003, pillar emplacement was set to begin in October and finish in December 2003 in the Eastern Sector; begin in January and finish in March 2003 in the Central Sector; and begin in March and finish in June 2004 in the Western Sector.[14] Pillar sites were determined through field assessment with the cooperation of the Parties by August 2003. The Parties received a set of marked maps indicating the location of proposed boundary pillars, stretching from the border with Djibouti in the east to the Salt Lake in the northwest, for comment. Eritrea endorsed the marked maps while Ethiopia did not reply.

When the 30-day period allowed under the Rules of Procedure for comment on the marked maps expired, “the Commission adopted specific boundary points that could serve as locations for the emplacement of pillars in that Sector”. Once the Commission was set to emplace pillars in the Eastern Sector and start demarcation in the Central and Western Sectors, however, Ethiopia refused “to allow demarcation to begin in the Central and Western Sectors” while Eritrea objected “to pillar emplacement in the Eastern Sector unless demarcation work was begun simultaneously in the Central and Western Sectors”. In addition, Eritrea informed the Chief Surveyor that it would “withdraw its arrangements for the provision of security in the Eastern Sector if the contract then under negotiation for the emplacement of pillars did not cover the entire boundary as determined in the Delimitation Decision”.[15]

Further, on 24 January 2003, Ethiopia submitted Comments stating that it had accepted the EEBC’s Decision on the understanding that the “straight-line segment between Points 6 and 9 (Badme line) would be refined during demarcation” to put Badme inside Ethiopia.[16] In the view of the EEBC, Ethiopia’s Comments “amounted to an attempt to reopen the substance of the April Decision”. It added that: “Notwithstanding the clarity with which the Commission has stated the limits upon its authority, Ethiopia has continued to seek variations to the boundary line delimited in the April Decision, and has done so in terms that appear, despite protestations to the contrary, to undermine not only the April Decision but also the peace process as a whole.” In these comments, “the Commission sees an intimation that Ethiopia will not adhere to the April Decision if its claim to ‘refinement’ of the April delimitation Decision is not accepted”.[17]

Ethiopia provided additional signals of its intention not to follow the EEBC’s Demarcation Directions. The UN Secretary General’s 6 March 2003 Progress Report on Ethiopia and Eritrea stated that Prime Minister Meles Zenawi has intimated to his Special Representative that “if its concerns were not properly addressed, Ethiopia might eventually reject the demarcation-related decisions of the Commission” and that his “Special Representative immediately consulted with the representatives of the Guarantors and Facilitators of the peace process, as well as the group of Friends of UNMEE, in Addis Ababa and in Asmara regarding Ethiopia’s position”.[18]

In its Observations issued in consideration of the comments advanced by the Parties on 24 January 2003, the Boundary Commission concluded that the Parties knew in advance, and agreed: “that the result of the Commission’s delimitation of the boundary might not be identical with previous areas of territorial administration”; “that it was not open to the Commission to make its decisions on the basis of ex aequo et bono considerations”; “that the boundary as delimited by the Commission’s Delimitation Decision would be final”; and that the Commission is “obliged to reject the assertion that it must adjust the coordinates to take into account the human and physical geography in the border region. Moreover, the Commission firmly rejects the contention that if such adjustments are not made the Commission’s work would be devoid of adequate legal basis”.[19]

These contentious exchanges were capped off by a turnaround. In a complete reversal and absolute contradiction of its declaration of 13 April 2002, Ethiopia informed the UN Security Council that the Commission’s Decision is “totally illegal, unjust and irresponsible”. The Prime Minister’s letter of 19 September 2003 went on to state that “It is unimaginable for the Ethiopian people to accept such a blatant miscarriage of justice. The decision is thus a recipe for continued instability, and even recurring wars”. It further asserted that “Nothing worthwhile can therefore be expected from the Commission to salvage the peace process”. Finally, the letter called on the Security Council to “set up an alternative mechanism to demarcate the contested parts of the boundary in a just and legal manner so as to ensure lasting peace in the region”.[20]

In a detailed and direct response, the EEBC described Ethiopia’s letter as “a repudiation of its repeated acceptance of the Commission’s decision since it was rendered”.[21] Similarly, the UN Security Council responded that “only the full implementation of the Algiers Agreements will lead to sustainable peace” and “that Ethiopia has committed itself under the Algiers Agreements to accept the Boundary Decision as final and binding”. The Security Council urged Eritrea and Ethiopia to abide by their commitments under the Algiers Agreements and to fully cooperate with the Boundary Commission in the implementation of its decisions.[22] It specifically called on “Ethiopia to provide its full and prompt cooperation to the Boundary commission and its field officers in order that demarcation can proceed in all sectors as directed by the Boundary Commission”.[23]

The UN Secretary General welcomed Eritrea’s continued cooperation with the Boundary Commission while criticising Ethiopia’s failure to extend the necessary cooperation in the exercise of its mandated functions.[24] In an attempt to resolve the impasse, he appointed, on 30 January 2004, Llyod Axworthy, former Canadian Minister of Foreign Affairs, as his Special Envoy to Eritrea and Ethiopia. In direct contradiction to its final and binding character, Axworthy had characterised the decision of the Boundary Commission under the Algiers Agreement as “something that has to be worked at” and “needs to be developed.”[25] Lacking an explicit statement of his mandate from the Secretary General to allay its suspicion, Eritrea refused to accept his good offices as an “alternative mechanism”.

Meanwhile, Ethiopia declared its acceptance of the EEBC Decision “in principle” and proposed a “five point peace plan” that, in the main, called for dialogue with Eritrea to amend the 13 April 2002 Delimitation Decision as a condition for the demarcation of the boundary. The ‘initiative’ was announced by the prime minister in an address to the Ethiopian parliament on 25 November 2004.[26] On the same day the proposal was presented in the 8th Session of the ACP-EU Joint Parliamentary Assembly, in The Hague, as a ‘major breakthrough’. In addition to my position as ambassador to the EU, I also served as the chief delegate of the Eritrean National Assembly to the ACP-EU Joint Parliamentary Assembly. I took the floor to comment on the new Ethiopian initiative in exercise of my right of response as the representative of Eritrea.

I stated that I have taken note of the announcement by the Delegate of Ethiopia; reminded the Joint Assembly that the Decision of the Boundary Commission is final and binding, to be implemented as is, as per the Algiers Peace Agreement; that the border would have long been demarcated were it not for Ethiopia’s persistent obstructions; and recapped that Ethiopia had accepted the EEBC Decision in April 2002, rejected it in September 2003, and says that it has accepted it ‘in principle’ now in November 2005, whatever that means? I asserted that the way forward is simple and straight: Ethiopia’s unequivocal acceptance of the Decision and full cooperation with the Boundary Commission to enable the physical demarcation of the boundary. Hence, time will tell whether this is a serious new ‘development’ leading to a real breakthrough or a mere public relations stunt. Finally, I assured the ACP-EU Joint Parliamentary Assembly that Eritrea will study the text of the proposal and declare its position in due course.[27]

In an attempt to end the impasse and “secure the resumption of the demarcation process”, the EEBC invited Eritrea and Ethiopia, on 4 February 2005, to a meeting in London on 22 February 2005 and urged them to enable it to complete its mission. Eritrea accepted the invitation and affirmed its willingness “to meet with the Commission and Ethiopia to discuss the unconditional renewal of the demarcation process.” On the other hand, Ethiopia declined the invitation to meet with the Commission and Eritrea without preconditions. In declining the invitation, Ethiopia claimed that meeting without prior “dialogue between the Parties” would be “premature”, “unproductive” and could have “an adverse impact on the demarcation process”.

Eritrea’s insistence on “adherence to the April 2002 Delimitation Decision” as final and binding was consistent with the terms of the Algiers Peace Agreement. Ethiopia’s demand for the modification of the Decision flouted the Agreement. Ethiopia’s inadmissible preconditions and demand, faced with Eritrea’s legitimate insistence, created an impasse and continued to disable the Boundary Commission from proceeding with the demarcation process.

The situation forced the Boundary Commission to overcome its previous reluctance “to express any legal assessment of the circumstances” which led to the “impasse” and “identify the conduct” that “prevented [it] from completing its mandate” to demarcate the border as delimited by the 13 April 2002 Decision:

Ethiopia is not prepared to allow demarcation to continue in the manner laid down by the Commission. It now insists on prior ‘dialogue’ but has rejected the opportunity for such ‘dialogue’ within the framework of the demarcation process provided by the Commission’s proposal to meet with the Parties on 22 February. This is the latest in a series of obstructive actions taken since the summer of 2002 and belies the frequently professed acceptance by Ethiopia of the Delimitation Decision. ... In view of the refusal of Ethiopia to attend the 22 February meeting, the Commission had no alternative but to cancel it.[28]

In exasperation, the EEBC conceded that it “does not see any immediate or short term prospect of the renewal of the demarcation process” and started taking immediate steps to close down its Field Offices. At the same time, it reaffirmed its readiness to reactivate them and resume its ground work if the deadlock is resolved:

These [Field Offices] can be reactivated (though subject to some months of lead time) if Ethiopia abandons its present insistence on preconditions for the implementation of the demarcation. As for the Commission, it remains ready to proceed with and complete the process of demarcation whenever circumstances permit.

The Commission must conclude by recalling that the line of the boundary was legally and finally determined by its Delimitation Decision of 13 April 2002. Though undemarcated, this line is binding upon both Parties, subject only to the minor qualifications expressed in the Delimitation Decision, unless they agree otherwise. Conduct inconsistent with this boundary line is unlawful.[29]

Subsequently, the UN Security Council called on Ethiopia “without preconditions, to start the implementation of demarcation, by taking the necessary steps to enable the Commission to demarcate the border completely and promptly”.[30] Yet, Ethiopia remained unwilling to accept the Delimitation Decision without equivocation, enable the physical demarcation of the boundary or meet its financial obligations to the Boundary Commission. Faced with Ethiopia’s refusal to budge and persistent reluctance to cooperate, an exasperated Boundary Commission announced, on 30 May 2005, that it had suspended all its activities, closed its Field Offices, and placed its field assets in the custody of UNMEE due to Ethiopia’s refusal to cooperate with its efforts to demarcate the boundary.[31] The situation remained unchanged and no demarcation activity was conducted during the rest of the year.

In an effort to break the impasse, the witnesses to the Algiers Agreement and the President of the Security Council issued similar statements on 22 February 2006 and 24 February 2006 (S/PRST/2006/10), respectively. The witnesses and the President reminded Eritrea and Ethiopia of their agreement to accept the delimitation and demarcation decisions of the Eritrea-Ethiopia Boundary Commission as final and binding and called on them to respect their commitments and cooperate with the Boundary Commission to implement its decision without further delay. In addition, they urged the Commission to convene a meeting of the Parties for technical discussions, and the Parties to attend the meeting and abide by the decisions of the Boundary Commission, in order to successfully conclude the demarcation process.

In the context of realpolitik, however, the scores of resolutions of the UN Security Council and the numerous statements of its rotating Presidency, underlining “unwavering commitment” to the peace process, to the full and expeditious implementation of the Algiers Agreements, and to the final and binding delimitation and demarcation determinations of the Eritrea-Ethiopia Boundary Commission, lacked coherent internal support and substantive authority to effectively persuade Ethiopia to cooperate with the Boundary Commission.[32] The UN Security Council lacked the convergence of interest, the unity of purpose, and the political will to honour its commitment and enforce its resolutions vis-à-vis the Eritrea-Ethiopia peace process.

The US, as the principal architect of the Algiers Peace Agreement, one of its witnesses, and the predominant actor of the Permanent Members (P5) of the UN Security Council, had initially supported the physical demarcation of the boundary on the basis of the Delimitation Decision. Caught up in the mix of a close regional alliance with Ethiopia in the ‘war on terror’ and tense relations obtaining with Eritrea originating basically in the latter’s refusal to address the issue of the continued detention of two Eritrean employees of the US embassy in Asmera, the US reversed its position, instructed Ethiopia not to allow the demarcation of the boundary,[33] and used its dominant position and enormous clout to abet Ethiopia’s non-compliance with its treaty obligations under international law.

It seems that the policy reversal was not without its sceptics within the administration. For instance, the then US Permanent Representative to the United Nations, Ambassador John Bolton stated, that “For reasons I never understood, Frazer [US Assistant Secretary for African Affairs] reversed course and asked in early February [2006] to reopen the 2002 EEBC decision, which she had concluded was wrong, and award a major piece of disputed territory to Ethiopia. I was at a loss to explain that to the Security Council, so I didn’t”.[34] Having persuaded Ethiopia not to implement demarcation and issued her internal directive referred to by the ambassador, Jendayi Frazer publicly suggested that ‘just and reasonable adjustments’ be made to the EEBC’s final and binding delimitation decision in demarcating the border.[35]

In any case, the Commission sought, in consideration of the advice of the witnesses of the Algiers Agreement and the President of the Security Council, to arrange a meeting with the Parties to try to secure their consent to the resumption of the demarcation process, interrupted in 2003, in early March 2006.[36] The meetings took place on 10 March and on 17 May 2006. At both meetings, the Boundary Commission operated on the premise that both states were “committed without condition or qualification to the full implementation of the Boundary Commission’s delimitation decision of 13 April 2002”.[37] At the March meeting, the Boundary Commission stressed the need to resume and complete the demarcation process without further delay to prevent the possible deterioration in the situation due to the deadlock. At the May meeting, the Commission advised the Parties of its intention to reopen immediately its field offices in Addis Ababa and Asmera as a first step to resume the demarcation process.

At the political level, the resumption of the demarcation process would require the full cooperation of the Parties with the Boundary Commission and their assurance of security for its field personnel. At the technical level, it would require re-staffing the offices, rehiring the surveyors, concluding contracts for the construction of the boundary pillars, and re-establishing the security arrangements to ensure the safety of the Commission’s field personnel, surveyors and contractors. Since Eritrea had submitted its security plan on 14 October 2003, the Commission repeated its request to Ethiopia to submit its security plan by 19 May 2006.

Further, at the 17 May 2006 meeting, the Commission proposed to resume demarcation once:

(a) The Commission can be assured that UNMEE will be retained in the area at a level sufficient to enable it to continue to provide the services to the field staff on at least the same scale that it has hitherto; (b) The parties can provide or, if already provided, confirm their proposed security arrangements; (c) Contracts can be concluded with the surveyors and the on-site contractors; (d) And most important of all, both the parties should cooperate fully with the Boundary Commission’s representatives in the field; (e) The Boundary Commission has set 15 June 2006 for a further meeting with the parties in the hope that this will help to develop the momentum.[38]

There was, however, no momentum. The Commission had to cancel the proposed 15 June 2006 meeting because Eritrea declined to attend it on the grounds that “Ethiopia still had not accepted the delimitation decision without qualification”.[39] On the same day, the Commission held an internal meeting, discussed the next steps, decided to reopen the field offices in Asmera and Addis Ababa as soon as possible, invited Eritrea and Ethiopia to a meeting on 24 August 2006, and asked them to reply by 10 August 2006.

The Commission sent teams in early August 2006 to reopen the field offices in the respective capitals. The team in Addis Ababa was denied formal reception and the team to Asmera was refused entry visa. Nevertheless, the field office in Addis Ababa was reopened with UNMEE’s assistance while that in Asmera remained closed.

Both Eritrea and Ethiopia failed to respond to the Commission’s invitation to meet on 24 August 2006. The lack of real progress in the demarcation process caused growing exasperation. Eritrea informed the Commission that Ethiopia’s public and unequivocal acceptance of the final and binding Delimitation Decision was necessary to work out the procedures of and arrangements for demarcation and avoid “another round of fruitless meetings”.[40] The Commission held an internal meeting from 22 to 24 August 2006 and scheduled another one in November 2006 to examine the situation and consider the best way forward to demarcate the boundary and conclude its mandate. Its efforts to resume the demarcation process were frustrated as Eritrea persisted in its demand for the demarcation of the boundary as delimited and Ethiopia stuck to its insistence for the modification of the Delimitation Decision prior to demarcation.

Under the circumstances, the UN Security Council adopted, on 29 September 2006, resolution 1710 (2006) calling on the Parties to “cooperate fully with the EEBC” and “to implement completely and without further delay or preconditions the decision of the EEBC and to take concrete steps to resume the demarcation process”. Specifically, the resolution demanded that “Eritrea reverse, without further delay or preconditions, all restrictions on UNMEE’s movement and operations” and that Ethiopia “accept fully and without delay the final and binding decision of the Eritrea-Ethiopia Boundary Commission and take immediately concrete steps to enable, without preconditions, the Commission to demarcate the border completely and promptly”.[41]

Further, the President of the Security Council issued a Press Statement, on 17 October 2006, expressing the Council’s “unwavering commitment to the peace process, including the full and expeditious implementation of the Algiers Agreements and implementation of the final and binding decision of the EEBC”.[42]

Subsequently, the Commission, in a letter dated 6 October 2006, asked the Parties “of the actions which each proposes to take to comply with the Council’s specific requests” and to respond by 22 October 2006. Ethiopia gave no reply while Eritrea’s reply on 22 October restated its previous position that Ethiopia’s unqualified acceptance of the EEBC’s Decision of 13 April 2002 was necessary for progress and insisted on the expeditious execution of the Award on the basis of the Commission’s Demarcation Directions. Again, both sides refused, Ethiopia in a letter dated 13 November 2006 and Eritrea in a letter dated 16 November 2006, the Commission’s 8 November 2006 invitation to meet on 20 November 2006 “to consider the further procedures to be followed in connection with the demarcation of the boundary between Eritrea and Ethiopia”.[43] Ethiopia’s letter contained criticisms which the Commission deemed necessary to answer.

In a direct response to Ethiopia’s letter of 13 November 2006 on 27 November 2006, the President of the Boundary Commission provided conclusive assessment of Ethiopia’s conduct in the demarcation process:

It is a matter of regret that Ethiopia has so persistently maintained a position of non-compliance with its obligations in relation to the Commission. ... Ethiopia has by its conduct on many occasions repeatedly obstructed the Commission’s field personnel and prevented them from carrying out the necessary investigations in the field and made a ‘cooperative process’ impossible.[44]

With its work frustrated by Ethiopia’s persistent non- cooperation, the Boundary Commission, by November 2006, abandoned its original plan to emplace boundary markers on the ground and decided to demarcate the boundary by a list of precise coordinates representing “the locations at which, if the Commission were so enabled by the Parties, it would construct permanent pillars” along the entire length of the boundary. Applying the concept of ‘institutional effectiveness’, relying on the authority of ‘international law’, and ‘guided by significant authority in State practice’, the Boundary Commission adopted ‘virtual demarcation’ as a viable legal option to circumvent the deadlock caused by persistent non-cooperation and effect the demarcation of the boundary. Having affirmed the legal basis of virtual demarcation as a technique, the Commission asserted its terrestrial accuracy as follows:

Modern techniques of image processing and terrain modelling make it possible, in conjunction with the use of high resolution aerial photography, to demarcate the course of the boundary by identifying the location of turning points (hereinafter called “boundary points”) by both grid and geographical coordinates with a degree of accuracy that does not differ significantly from pillar site assessment and emplacement undertaken in the field. The Commission has therefore identified by these means the location of points for the emplacement of pillars as a physical manifestation of the boundary on the ground.[45]

The Commission provided the Parties with the list of the boundary turning points accompanied by forty-five 1:25,000 scale maps illustrating the boundary points; gave the Parties 12 months up to the end of November 2007 to demarcate the border; and advised that:

If, by the end of the period, the Parties have not by themselves reached the necessary agreement and proceeded significantly to implement it, or have not requested or enabled the Commission to resume its activity, the Commission hereby determines that the boundary will automatically stand as demarcated by the boundary points listed in the Annex hereto and that the mandate of the Commission can then be regarded as fulfilled. Until that time, however, it must be emphasised that the Commission remains in existence and its mandate to demarcate has not been discharged. Until such time as the boundary is finally demarcated, the Delimitation Decision of 13 April 2002 continues as the only valid legal description of the boundary.[46]

In the definitive assessment of the Boundary Commission, Ethiopia’s conduct in the demarcation process, both at the political and technical levels and particularly, its systematic and persistent non-cooperation, obstructed the physical demarcation of the boundary. Its non-cooperation constituted a clear violation of its commitment to accept the delimitation and demarcation decisions of the Boundary Commission as final and binding under the Algiers Agreement.

For its part, Eritrea initially cooperated fully with the Boundary Commission. It later started to raise obstacles mainly in reaction to Ethiopia’s conduct and in protest of the Security Council’s failure to address effectively Ethiopia’s obstructions. In response to Ethiopia’s refusal to allow fieldwork in the Central and Western Sectors, Eritrea objected to demarcation in the Eastern Sector unless it continued in tandem with the work planned along the entire boundary. It also imposed restrictions on UNMEE’s freedom of movement that affected the Mission’s ability to provide necessary assistance to the Commission’s field staff.[47]

Given the character and impact of the comparative obstructions, the Boundary Commission put the blame for its inability to demarcate the boundary by emplacing permanent pillars on the ground squarely on Ethiopia’s conduct. In indirectly conceding its non-compliance with the terms of the Algiers Agreement, Ethiopia complained that Eritrea was also guilty of the same obstruction. In the matter of appraising the actual conduct of the Parties and apportioning blame for disabling the Boundary Commission to demarcate the boundary on the ground as delimited by the 13 April 2002 Decision, it is illustrative to quote at length from the commission’s letter responding to Ethiopia’s complaints:

One of the elements in Ethiopia’s complaints is that Eritrea is guilty of the same obstruction. Eritrea’s non-cooperation with the Commission only really developed after Ethiopia insisted that the boundary should be altered to meet with what Ethiopia chose to call ‘anomalies and impracticalities’, despite the clear statements of the Commission that this could not be done. When asked to confirm its continuing acceptance of the delimitation Decision, Ethiopia repeatedly qualified its position by saying that it wished negotiations to take place regarding such ‘anomalies and impracticalities’. Eritrea’s insistence on strict adherence to the terms of the Delimitation Decision was a position which it was entitled to adopt in accordance with the Algiers Agreement.

You place great emphasis on the ‘need for dialogue and support by neutral bodies to help the two Parties make progress in demarcation and normalisation of their relations’. Of course, ‘the normalisation of relations’ is a desirable objective but that is a matter that falls outside the scope of the Commission’s mandate, which is solely to delimit and demarcate the border. The scope for ‘dialogue’ is limited to what is necessary between the Commission and the Parties to further the actual process of demarcation on the ground. There is no room within the framework of the Algiers Agreement for the introduction of ‘neutral bodies’ into the demarcation process.

You ask ‘Why has the Commission abruptly and without notice chosen to abandon the process for demarcation embodied in its rules, instructions and decisions?’ The answer is that the Commission has been unable to make progress, initially, because of Ethiopia’s obstruction and, more recently, because Eritrea has followed a similar course.

Your letter seeks to blame the Commission for Ethiopia’s failure to meet its obligations under the Algiers Agreement. Such blame is entirely misplaced. The truth of the matter appears to be that Ethiopia is dissatisfied with the substance of the Commission’s Delimitation Decision and has been seeking, ever since April 2002, to find ways of changing it. This is not an approach which the Commission was empowered to adopt and is not one to which the Commission can lend itself.[48]

The UN Secretary General fully shared the assessment of the EEBC of Ethiopia’s singular failure to respect its commitments under the Algiers Agreement and cooperate with the Commission in the demarcation process in accordance with the Delimitation Decision:

Ethiopia’s refusal to implement - fully and without preconditions - the final and binding decision of the Boundary Commission remains at the core of the continuing deadlock”. I therefore strongly urge the Government of Ethiopia to comply with the demand of the Security Council, expressed in resolution 1640 (2005) and reiterated in resolution 1710 (2006). Full implementation of the latter resolution remains key to moving forward the demarcation process and to concluding the peace process.[49]

The EEBC made a final attempt to revive the demarcation process by convening a meeting with the Parties on 6-7 September 2007 “to consider how pillars may be erected along” the boundary points of the November 2006 line of virtual demarcation.[50] In preparation for the meeting, the Commission had, on 27 August 2007, circulated to the Parties an Agenda specifying the conditions each Party was required to satisfy in order to enable it to resume its activities.

Eritrea was required “to lift restrictions on UNMEE insofar as they affect the EEBC; to withdraw from the Temporary Security Zone (TSZ) insofar as the present position impinges on EEBC operations; to provide security assurances; to allow free access to pillar locations.” For its part, Ethiopia was required “to indicate its unqualified acceptance of the 2002 Delimitation Decision without requiring broader ranging negotiations between the Parties; to lift restrictions on movement of EEBC personnel; to provide security assurances; to meet payment arrears; to allow free access to pillar locations.”[51]

In his opening statement, the President of the Commission reminded the Parties of “the list of locations identified by the Commission for boundary pillars using coordinates accurate to within one metre, which took into account the observations of the Parties”; observed that had the Commission “been able to go on the ground in the way originally planned, this is where the pillars would have been fixed, subject to the processes outlined in the Demarcation Directions”; expressed “hope that this indication of the adjusted line would enable the Parties to take a more positive approach to demarcation on the ground as they would see what [we] had in mind”; noted that the Parties had “less than three months now” left out of the previously given “twelve months to consider their positions and seek to reach agreement on the emplacement of pillars;” and acknowledged that Eritrea’s letters of 5 September 2007 “contain significant indications of willingness to see the process of demarcation resumed.”

In the trilateral exchanges during the meeting, Eritrea affirmed its readiness to meet the stated conditions required to enable the Commission to resume its activities while Ethiopia failed to do so and presented, instead, a series of observations which did not directly respond to the specified agenda items.[52] The meeting ended without progress. In his concluding remarks, the President of the Commission reminded the Parties that “the demarcation by coordinates identifying with precision the locations where pillars should be in place will become effective at the end of November unless in the interval the Parties act so as to produce a new situation” and stated that “we greatly regret that we could not take our work through to its full conclusion, but at least we leave you with a line that is operable”.[53]

The 30 November 2007 deadline arrived with no progress attained towards the construction of boundary pillars in the manner anticipated by the Commission. Ethiopia declined the EEBC’s request to appoint a substitute for Sir Arthur Watts, one of the EEBC’s Commissioners originally appointed by Ethiopia, who died on 16 November 2006, as required by the Commission’s Rules of Procedure. It also remained, in defiance of repeated requests by the Commission to meet its financial obligations, in arrears in payment of its share of the Commission’s expenses in breach of the Algiers Agreement.