With the increasing number of women joining the war in the 1970s, “Equal rights through equal participation” represented an emergent motto toward the emancipation of women from rigid traditional and patriarchal societal norms. The Eritrean liberation movement recognised the fundamental importance and potential role of gender equality and women’s empowerment as an integral part of the vision for a progressive, democratic and developed Eritrean society after independence.

Post-independence, the promise of emancipation and gender equality has not materialised. Following their immersion and experience in a culturally progressive and revolutionary movement during the war, women returning from the field faced difficulties in reintegrating, as the societal and familial structures had remained relatively unchanged. Upon demobilisation, the betrayal of the promise and the resultant lack of assistance left former women fighters in a precarious situation: they were caught between expectations of equality and progress and the harsh societal realities of tradition and patriarchy. Following the conclusion of the liberation war, the revolutionary ideals of gender equality and emancipation, which lacked genuine commitment in the first place and were conveniently abandoned later, could not, in the absence of effective Front and government support, compete with the conservative patriarchal norms of traditional Eritrean society. Over time, gender equality and women’s emancipation in Eritrea became increasingly neglected. This article discusses five key factors that stand out in particular as facilitating this downward trajectory:

1. The reversion to traditional Eritrean societal norms that emphasised female domesticity;

2. The shift in national priority from liberation to nation-building and economic development;

3. Failure to build institutions as well as ratify and implement relevant legislation;

4. Inability to ensure equal participation and opportunity;

5. The Ethio-Eritrean border war and indefinite national service.

1. Reversion to Traditional Female Domesticity

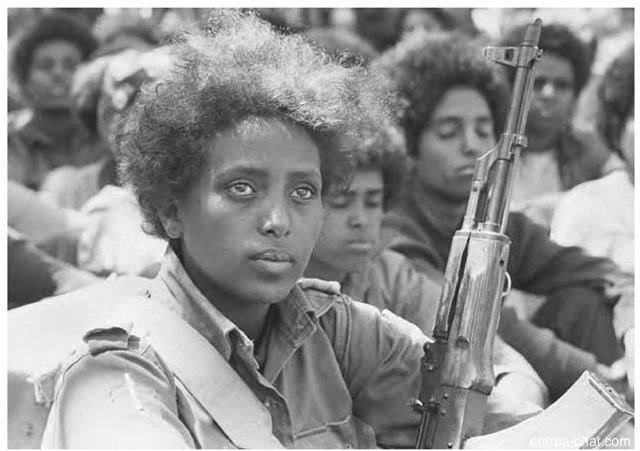

As previously indicated, Eritrean society before the liberation war was deeply rooted in tradition, with specific role expectations for men and women across cultural, familial and societal contexts. Eritrean society lays heavy emphasis on the domesticity of women, confining their responsibilities to tending to husband, children, and the home. Women were emancipated from their restricted roles during the liberation struggle, helping not only to shoulder the burden of the war, but also to carry the struggle forward over three decades. What is unique about the Eritrean case for independence is the high number of women engaged as fighters (including intelligence and espionage), in addition to vital civilian and semi-civilian roles. Women took on a wide range of roles across a wide spectrum of fields and services such as medical, educational, administrative, agricultural, construction and combat engineering. However, the assimilation of women in the military was not without its difficulties and resistance. Faced with prevailing prejudices and stereotypes, women faced an uphill battle for recognition and equality. Proving themselves through heroic action in combat, women in the lower ranks were integrated into the communal lifestyle of military culture, even taking on the appearance of their male compatriots in uniformed shorts and afros. Yet women were unable to ascend ranks and, therefore, absent from the higher echelons of decision-making.

After independence, demobilised women found themselves confronted by the expectations and pressures of traditions and customs that had remained virtually intact. The Front’s progressive social and cultural revolution that young women had participated in and become accustomed to in the field did not carry over into civilian society post-independence. With the demobilisation and return of many thousands of men came the reversion to the patriarchal system that assigned women to the subordinate position, placing the domestic burden on women; especially women from rural, nomadic or poor backgrounds.

2. The Rhetoric of Nation-Building and Economic Development

The shift in national priority from liberation to economic development, more evident in the regime’s rhetoric than practice, worsened the disparities faced by women. Nation-building and kick-starting economic development required professionals with higher levels of education and skills, for instance administering public institutions, managing parastatals and running businesses. While efforts were made by the Front during the struggle to improve the education and training of women, the skills they acquired were specific and necessary within the context of the liberation struggle. Women who were able to support themselves through their enrolment in the military during the armed struggle, once demobilised, found themselves without opportunities or prospects. There were no support structures such as financial welfare or professional training to facilitate the transition and re-integration of veteran women into society towards self-sufficiency. Lamentably, veteran women (and men) fighters who were disabled, suffered from mental health problems, or were now too advanced in age due to their service and sacrifice over years and decades, found themselves unceremoniously forgotten and marginalised by the incumbent regime in post-independence Eritrea. As for the rest of women in society – they were, once again, knocked back into domestic roles.

3. Failure to Build Institutions and Adhere to the Rule of Law

The vital role women played during the liberation struggle was acknowledged in the preamble of the 1997 Eritrean Constitution that has yet to be implemented:

Noting the fact that the Eritrean women's heroic participation in the struggle for independence, human rights and solidarity, based on equality and mutual respect, generated by such struggle will serve as an unshakable foundation for our commitment to create a society in which women and men shall interact on the bases of mutual respect, solidarity and equality;

The Constitution also sets out guarantees of gender equality in all spheres of national life for women and bans all forms of discrimination. Of the 50 members that drafted the Constitution following independence, 21 were women, a promising beginning for gender empowerment and participation in the future of Eritrea. These aspirations were also reflected in the quota system of the National Assembly with 30% of seats reserved for women but falling short with 22% occupancy. This same high level of women’s participation was absent in the Executive branch, with only three female ministers compared to twenty male counterparts. However, without appropriate legal or institutional safeguards, the process of post-independence Eritrea’s democratic transition was gradually circumvented through the systematic centralisation and concentration of power in the President; leaving the question of gender equality in the Executive as moot. Like the 1997 Constitution, the promises of gender equality and women’s empowerment were also to remain but dry ink on paper.

4. Inability to Ensure Equal Participation and Opportunity

The Constitution (once implemented), together with the Marco-Policy framework and the National Charter for Eritrea were to provide the legal, economic and political foundations from which to jump-start the economy, consummate nation-building and construct the State of Eritrea. The National Charter also set out the basis for a constitutional political system based on respect for the rule of law, human rights, democracy, justice and fundamental freedoms, which were indispensable to the uplifting of the human condition in Eritrea. In line with the original aspirations of the struggle, the National Charter also identified six basic principles, those of national unity, active participation of citizens, the decisive role of the human factor, struggle for social justice, self-reliance, and a strong relationship between the people and the leadership. On paper, it seemed the necessary groundwork had been laid; in reality, however, it did not translate into practice. This is evident in the lack of representation or political participation of women in positions of power and influence, with its long-term negative consequences across all levels of society. Women absent from policy- and decision-making structures cannot defend women’s rights or push forward policies and funding on specific issues affecting women in society such as education, healthcare and welfare.

Recognising this gap, the mandate of the National Union for Eritrean Women (NEUW) after independence was to defend the rights and ensure equal participation of women, as well as advocate for gender equality across all sectors of society, especially in education, pay and opportunities. When NEUW’s was founded by the Front in 1979, its mandate was different. Initially, its mandate was to mobilise, unite and organise women in the service of the war of liberation. Its responsibilities were later expanded with the need to provide vital social services to orphans, pregnant fighters, refugees and the internally displaced. Significantly, the NEUW was conceived as a top-down initiative emanating from a male-dominated leadership and was not in control of setting its own agenda based on identified women’s interests and issues. As a consequence of this structure, the prioritisation of achieving liberation was pursued as the pre-condition to gender emancipation and empowerment. With the activities and capacity of the NEUW dependent on the interests of those higher up the chain of command, achievements and progress have been limited since independence. Scrutinising its progression from its design and execution, it becomes apparent that NEUW was ill equipped from its very inception to pursue its mandate of women’s equality and empowerment.

From an economic and socio-cultural perspective, barriers against the emancipation and empowerment of women still need to be redressed. Like certain customary laws, the Constitution enshrines equal rights of men and women to own property, including land in usufruct. However, bad governance, rampant corruption and mass impoverishment have hindered most women’s (and men’s) access to land. Other detrimental practices that have negative long-term impacts on the emancipation and empowerment of girls and women are female genital mutilation (FGM) and child marriage. With a legacy of devastating physical, mental and social repercussions on girls and women, steps have been taken to abolish the practice in Eritrea with declining trends reported. Similarly, child marriage is harmful as it forces young girls into a subordinate position under absolute male domination, often treated as property and falling victim to domestic violence and abuse. Foremost, the freedom and choice of girls are curtailed, from early and unwanted and harmful pregnancies, to preventing girls from finishing their education and pursuing economic opportunities, marginalising young women and perpetuating cycles of poverty. This interplay of barriers and detrimental customs present a huge challenge for young girls and women that have long-term ramifications affecting political participation, levels of development and economic prosperity.

5. The Ethio-Eritrea Border War and Indefinite National Service

The outbreak of the 1998-2000 Ethiopian-Eritrean border war called upon demobilised women fighters, as well as a new generation of young women fighters and civilians to support the war effort. Similar to the preceding war, women took on a multitude of jobs and functions, again, beyond the scope of traditional gender roles from the medical to manufacturing sectors. The participation of women across sectors of society, their immense efforts and sacrifices, nurtured expectations of equal rights even greater than the generation that served before.

Regrettably, when the dust of war settled, the expectations and promises of equality and empowerment failed to carry over, once again to the socio-economic and political spheres. The decline of women’s rights and equality was influenced by an interplay of factors: the purported priority to rebuild and develop the country after the war, a powerful conservative societal structure, and the failure of the incumbent government to legally enshrine women’s rights and implement complementary socio-political and economic policies. The dynamics of society and the subordinate place of women, however, are advantageous to the incumbent regime (which is already systematically and brutally oppressing the people), as societal structures self-regulate, monitor and oppress at least half the population. This is because women are less likely or unable to make demands and participate democratically and politically if there is no platform from which to unite, speak or be heard.

The state of ‘no war no peace’ with Ethiopia provided the incumbent regime with the pretext to pervert and extend the national service system indefinitely. Eritrea is also one of a handful of countries that drafts female soldiers, but does so forcefully and often recruiting underage girls (and boys) still in secondary education through ‘ግፋ’.[1] Those who make it to their final year in secondary school are automatically enrolled in the national service, facilitated through the meticulous records of the coupon rationing system and communal surveillance that alert the authorities of any efforts to evade. Severe punishment, detention or execution is usually dispensed to the evader if caught. Alternatively, immediate family members are often targeted and harshly punished, detained or heavily fined.

Recurrent reports recount widespread gender-based violence against female recruits, detailing systematic brutal treatment, abuse, torture, coerced servitude, sexual violence and exploitation committed with impunity while in training centres or in indefinite military service. The absence of institutional and legal mechanisms for recourse to ensure the protection and safety of women in service has been one of the key drivers pushing women to flee the country. Women who flee are also extremely vulnerable to gender-based violence and abuse, with survivors reporting horrific ordeals and experiences as they journey in search of asylum.

Alternatively, women who endure or are unable to flee national service, often become pregnant. They are then discharged, ostracised by family and community, and left to survive on the margins of society. The disruption of their secondary education and the absence of a viable labour market leave women unable to find decent or stable employment, perpetuating a cycle of a deteriorating standard of living and increasing poverty levels.

In an effort to alleviate poverty, microfinancing schemes aimed at women have been deployed. Microfinancing can provide an immediate source of income for survival and serve as an effective tool for development, but it is not in itself a vehicle for prosperity. The commitment of the entire system is vital, as familial and societal support together with government led initiatives and policies work to create a conducive environment that encourages economic growth and development. Women’s rights and empowerment are inextricably linked to achieving development and economic growth and are inextricably linked to their emancipation and participation at all levels, social, political and economic, for the seeds of progress to germinate, flourish and bloom.

For example, at the local level, gender barriers that are deeply rooted in traditional and familial expectations can clash with emancipation by frustrating women’s opportunities for gainful employment and financial independence. Remedying it requires implementing complementary political and social policies and removing detrimental practices at the governmental level. The most destructive example of which is indefinite national service which violates the right to normal family life and is systematically destroying the very fabric of Eritrean society, with husbands and wives, and children cut-off from their parents. Indefinite national service is denying any and all opportunities for youth to higher education and gainful employment, sentencing young men and women to toil away in never-ending and back-breaking manual jobs needlessly requiring hard intensive physical labour. Without an honest scrutiny of the root problems, programmes such as microfinancing serve as short-term bandage, maintaining a much larger system oppressing and condemning women to their fate in the first place.

Youth are an invaluable resource whose vital energies and creative potential are being mismanaged, wasted and squandered in indefinite national service. This bleak and harsh reality has spurred the exodus of generations of young men and women, fuelled by only two stark choices: either remain in indefinite service with no prospect of a future or normal life, or flee facing horrific ordeals with no guarantee of survival or a better life.

Indefinite national service in Eritrea amplifies the extreme vulnerability of young girls and women to gender-based violence. This stems from the structure of the military and national service, with women confined to a subordinate position under male superiors who are bestowed with the power to dictate all aspects of their daily life from rewards to punishment, with limited supervision or accountability. The absence of mechanisms or procedures for due recourse or protection leave women exposed to appalling mistreatment with impunity; magnifying the severity of the situation women in national service find themselves in.

The historical commitment, service and sacrifice made, not once but twice, by Eritrean women, has been abysmally reciprocated in the treatment of women in post-independence years. The calls for emancipation, empowerment towards gender parity were only invoked during times of war, when need and convenience were greatest. Alas, when the dust of war settled and business as usual set in, only the empty shells of promises remained.

The question of gender equality, emancipation and empowerment is ultimately an integral part of the overall question of democracy in Eritrea. Otherwise, the authoritarian regime has inexorably progressed towards near gender equality in the denial of basic rights because men and women have become equal in having no rights.

---------------------[1] ግፋ (Gifa) – Soldiers are regularly deployed to patrol the streets and search homes, without search warrants, to round-up any young boys and girls they find and enlist them in the army without parental consent or notification.