Eritrea: Human Rights Violations and their Pervasive Impact

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is a seminal legal document that lays the groundwork for the basic principles of human rights and embodies the universal values shared by the international community. Although it imposes no legally binding obligations on State parties, the declaration has served as a foundation for the development of numerous treaties, national and international laws, and institutions promoting and protecting human rights. In a very real sense, it has profoundly influenced the evolution of international human rights law.

This piece provides a brief overview of (1) the meaning of human rights, including civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights; (2) the state of human rights in Eritrea; (3) the impact of the ‘gross, systematic and widespread violations’ of human rights of the Eritrean people, and (4) the need for restorative justice and national reconciliation moving forward.

1. Basic Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms

2. State of Human Rights in Eritrea

3. The Pervasive Impact of the Violations of the Human Rights of the Eritrean People

4. The Imperative for Restorative Justice in a New Eritrea

1. Basic Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights has served as the foundation for two legally binding covenants, namely, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) adopted on16 December 1966 and the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) also adopted in 16 December 1966. The ICCPR came into force on 23 March 1976 while the ICESCR came into force on 3 January 1976. The two international covenants, and their respective protocols, are the culmination of years of negotiations in the context of the West-East divide. Collectively, the Universal Declaration and the two Covenants constitute the foundation for the International Bill of Rights.[1]

There are nine core international human rights instruments. A specific committee of experts has been set up to monitor the implementation of each instrument. Eritrea is a party to six of these nine international human rights instruments.[2] There are also numerous other universal instruments relating to human rights.[3]

Obligations and Duties of a State Party

Upon signing and ratification of an international human rights treaty, a State becomes party to the treaty and assumes “the obligations and duties under international law to respect, to protect and to fulfil human rights. The obligation to respect means that States must refrain from interfering with or curtailing the enjoyment of human rights. The obligation to protect requires States to protect individuals and groups against human rights abuses. The obligation to fulfil means that States must take positive action to facilitate the enjoyment of basic human rights.”[4] (Emphasis added).

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights imposes direct obligations and specific responsibilities on State Parties. Article 2(1) requires a State Party “to respect and to ensure to all individuals within its territory and subject to its jurisdiction the rights recognized in the present Covenant, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status”.

Complementing these civil and political rights, Article 2(1) of the International Covenant of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights requires a State Party “to take steps, individually and through international assistance and cooperation, especially economic and technical, to the maximum of its available resources, with a view to achieving progressively the full realization of the rights recognized in the present Covenant by all appropriate means, including particularly the adoption of legislative measures”.

The fulfilment of economic, social and cultural rights demands the allocation of substantial resources, entails significant redistribution of social goods and services, and strains public finances. Recognising the reality of resource constraint, the Covenant advises the progressive realisation of these rights through an incremental process. Beyond resource availability, the cumulative realisation of these rights requires commitment to social justice driving a State to take appropriate measures to the maximum of its ability. Otherwise, lack of resources cannot justify inaction or indefinite postponement of measures to avail these rights. This perspective, together with the historical evolution of the two Covenants put emphasis on and gave priority to political and civil rights rather than economic, social and cultural rights. The 1993 Vienna Declaration[5] rectifies this imbalance by reaffirming that “[a]ll human rights are universal, indivisible and interdependent and interrelated’ and the ‘the international community must treat human rights globally in a fair and equal manner, on the same footing, and with the same emphasis.”

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights recognizes that certain rights are absolute (cannot be limited for any reason) and are non-derogable (cannot be suspended) even during times of ‘public emergency which threatens the life of the nation and the existence of which is officially proclaimed’.[6] In concise terms, these absolute and non-derogable rights include:

Article 6 –

Right to life.

Article 7 – Freedom from torture.

Article 8 – Right to not be enslaved (inc. ‘forced or compulsory labour’)

Article 11 – Right to not be imprisoned merely on the ground of inability to

fulfil a contractual obligation.

Article 15 –

No one can be guilty of an act of a criminal offence which did not constitute a

criminal offence.

Article 16 – Right to recognition as a person before the law.

Article 18 –

Right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion.

2. State of Human Rights in Eritrea

Eritrea today is a specimen of a broken society, a society broken by the objective consequences of the deliberate policies and practices of an oppressive regime preoccupied with survival and self-aggrandisement. Generations of Eritreans have waged a long and hard struggle for national liberation and made huge sacrifices for liberty, democracy and prosperity. Yet, the authoritarian regime has betrayed these noble objectives. Its amply documented record of ‘gross, systematic and widespread violations’ of human rights has aggravated the devastation of the country and the misery and impoverishment of the people wrought by a century of foreign occupation, colonial plunder and neglect as well as three decades of a war of national liberation and two years of a war of national defence. Life for the vast majority of Eritreans has degenerated to a preoccupation with the search for daily bread and survival at the lowest rungs of contemporary global society.

Nearly three decades post-independence, the authoritarian regime has nothing to show for its years in power. It has failed to establish a democratic system of government that vindicates the immense sacrifices and meets the age-old yearnings of the people for peace, justice and prosperity. Unable to provide for the basic needs of the people, the authoritarian regime continues to ride roughshod over the country. Brutal repression manifest in its gross, systematic and widespread violations of human rights, economic hardship and indefinite active national service, continue to drive the mass exodus of Eritreans, especially the youth, out of the country. Stripped of their civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, the Eritrean people seek deliverance from an abominable regime and aspire to build a free, democratic and prosperous society.

i. Rule by Fear: Arbitrary Arrests, Enforced Disappearance, Torture

The regime has built a system based on multiple layers of monitoring and strict population control enforced by gross, systematic and widespread violations of human rights to instil fear in the general population, force compliance and keep a tight grip on every aspect of national life.

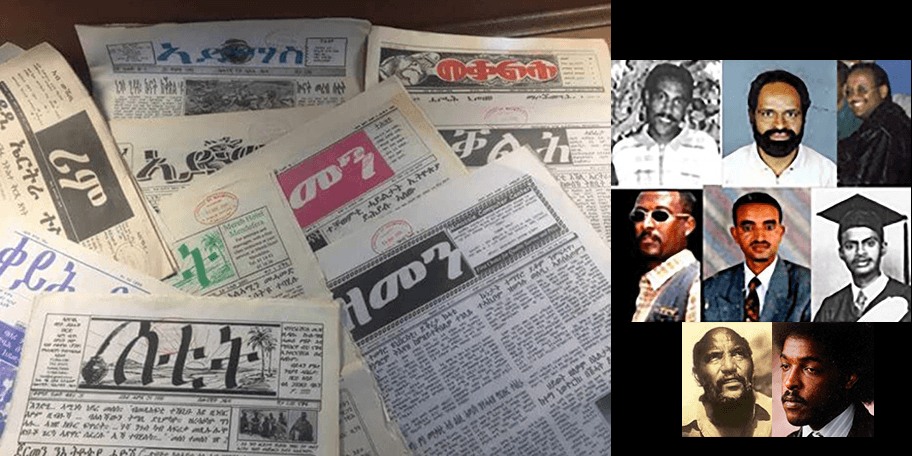

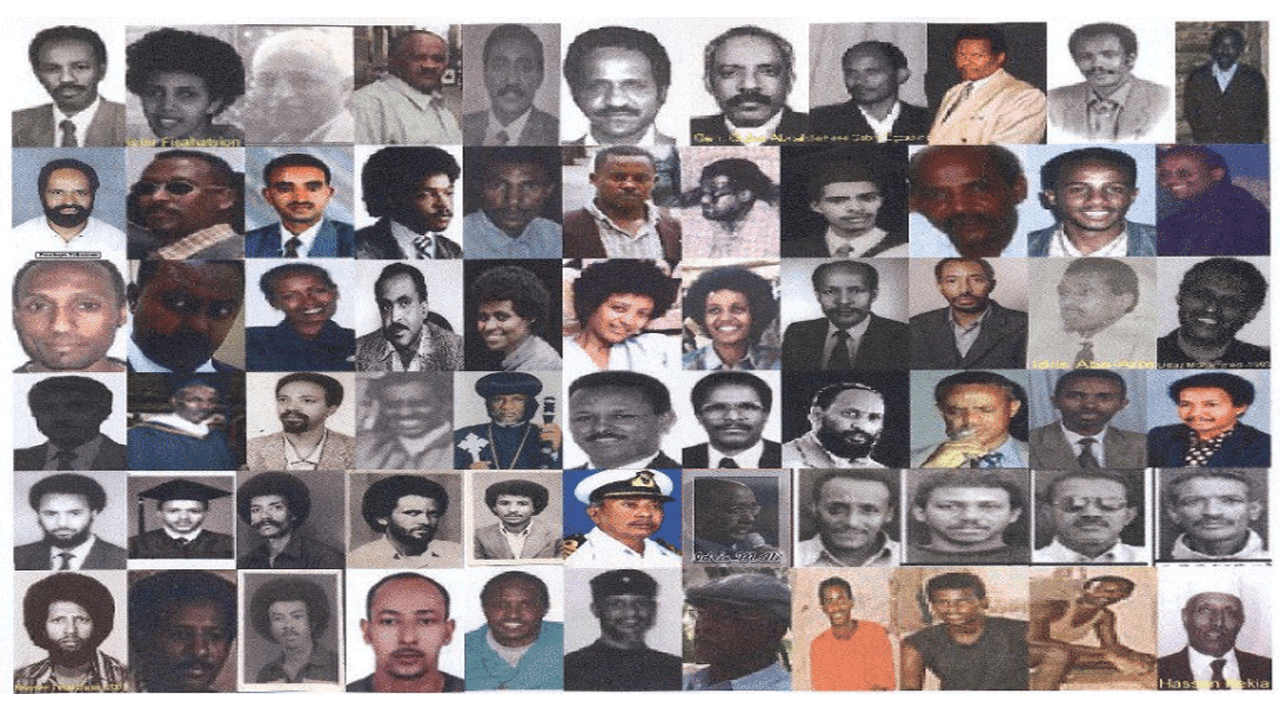

The mandate of the Transitional Government expired with the ratification of the Constitution of Eritrea in May 1997. Ever since, the President has illegally usurped state power and arbitrarily extended his tenure. The brutal crackdown, arbitrary arrest and indefinite detention, in violation of due process and without formal charge or trial, of senior government officials and journalists on 18 September 2001 has enabled the president to personalise power. This has been attained through arbitrary arrests, constant purges, indefinite detention and enforced disappearances using an expansive security apparatus and an extensive network of spies and informants. Thousands of Eritreans have been denied the right to life; freedom from torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment; the right to liberty and security of the person; the rights of detainees; equality before the courts;, right to recognition as a person before the law; and freedom from arbitrary or unlawful interference. As human rights are interconnected and interdependent, certain denials violate several human rights simultaneously.

Arbitrary detention, enforced disappearance, torture, cruel and inhuman treatment are widespread practices ruthlessly meted out to supress and punish Eritreans who seek to exercise the right of freedom of thought, conscience and religion or freedom of opinion or expression. Human rights are violated with impunity. Fear of being monitored, reported or accused of criticising, dissenting or discussing certain issues, in the context of harsh repression, has sown widespread distrust among friends, neighbours and even family members. Self-censorship has become the default mode for many citizens at home and, often, even abroad. Regime propaganda packages the silence induced by harsh repression, retribution and pervasive fear as ‘consent’.

The state owns the media (radio and television) and controls the message (content and delivery information). This has enabled the regime to construct a singular ‘official’ narrative, externalise blame and fabricate pretexts for its failures to feed its propaganda.[7] Independent media have been banned to prevent an alternative source of information and preclude the possibility of public scrutiny and demand for accountability, encouraging popular engagement, and challenging the regime’s singular narrative.

General Comment No. 34 on Article 19 of the ICCPR stresses that freedom of opinion and freedom of expression are closely related, ‘essential for any society’ and the ‘foundation stone for every free and democratic society’. The two freedoms are crucial instruments in the advocacy for accountability, transparency and the promotion and protection of human rights. It is integral to the enjoyment of subsequent rights such as freedom of assembly and association, and the right to vote. Freedom of expression includes ‘political discourse’, commentary on ‘public affairs’, ‘discussion of human rights’, ‘journalism’, ‘cultural and artistic expression’, ‘religious discourse’ including forms of expression such as ‘spoken, written and sign language’, ‘images’, ‘books, newspapers, pamphlets, posters, banners’ as well as ‘forms of audio-visual’, ‘electronic and internet-based modes of express’.[8]

The relation between freedom of opinion and expression and the media is essential to the fulfilment of the other rights in any society. This includes the right of public and media access to information or records on public affairs held by designated public bodies or those carrying public functions. Such public bodies include the executive, legislative and judicial branches of the State as well as other national, regional, local public or governmental authorities.

The regime deliberately denies the right of access to information on crucial matters of public interest and policy. It avails no information regarding its annual budget, revenues or expenditures and publishes no macroeconomic data or performance indicators for the various economic and social sectors. There exists no forum for national discourse on the real issues, pressing challenges and urgent problems facing Eritrean society. The suspension of the Eritrean National Assembly allows the president to squander national resources, including the revenues from the lucrative mining sector, at whim without due scrutiny and accountability.

The fate of the detained senior officials is a harrowing example of the regime’s tight control of a singular narrative. While labelling them as traitors and collaborators with a foreign enemy, it has brought no official charges against them. Initial attempts to interrogate and challenge the regime’s singular narrative were brutally suppressed. The emasculation of the judiciary, the denial of legal recourse and the lack of access to legal counsel have become the standard in Eritrea, driving widespread detentions without charge or trial. Detention under a notorious practice of ‘keep this one for me’ atsnhaley (ኣጽንሓለይ) in which any officer puts an ordinary citizen or national service conscript in prison at whim and leaves him/her there until he decides, if he remembers at all, to release them has become prevalent. Family and friends who ask questions about the detainees are harassed, threatened with violence or experience the same fate. Individuals arbitrarily arrested and denied their right to due process or a means of redress are denied their right to liberty and security of the person (ICCPR, Art. 9), the right to equality before the courts (ICCPR, Art. 14), and right to recognition as a person before the law (Art. 16).

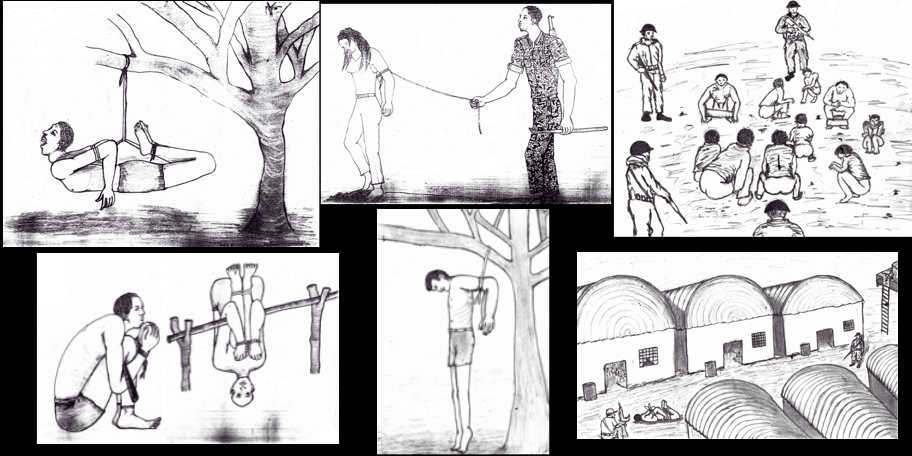

The regime’s perpetration of ‘enforced disappearances’ violates the right to life (ICCPR, Art. 6). The deprivation of liberty, the refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of said liberty and the concealment of the affected individual’s fate pose a great threat to life.[9] Essentially, enforced disappearances place the individual outside the limits of protection of the law and, with it, accountability for his/her care. This results in numerous subsequent human rights violations, such as the freedom from torture and inhuman treatment (Art. 7). Torture and other cruel, inhumane and degrading treatments and punishments are systematically and extensively used in ‘detention centres including military, civilian, official and unofficial’ in atrocious conditions.

Detention and use of torture are reportedly common means of obtaining information, dispensing punishment for alleged wrongdoing of oneself or others. Torture techniques reportedly include: “beating with whips, plastic tubes and electric sticks, standing [outside] on a very hot sunny day at noon, tying the hands and feet like the figure of eight, tying the hands and feet backwards, tying to trees, forcing the head down into a container with very cold water, beating the soles of the feet and the palms. In addition, the interrogator is allowed to use whatever fantasy comes to his mind…”.[10] Examples include the use of ‘electric shocks, mock drowning, mock burials and executions, various forms of sexual torture, and extensive exposure to the scorching sun’ and techniques known as “Helicopter”, “Otto”, “Jesus Christ Crucifixion”, “Almaz”, “Torch”, “Ferro”, and “Gomma”. Deaths have been reported as a result of torture and inhumane conditions of detention. Detention in overcrowded metal containers that reach extremely high temperatures during the day and freezing point at night is used throughout the country.

Furthermore, the authoritarian regime bans certain religious groups, interferes with freedom of faith, restricts freedom of worship and persecutes religious leaders. It recognises only four religious communities: Eritrean Coptic Orthodox, Sunni Islam, Roman Catholic, and Evangelical (Lutheran). Followers of unrecognised religions face restrictions ‘to the practice of their religions’ and are systematically persecuted.[11] Even leaders and followers of the four recognised religious communities have also been targeted, arrested and victimised by the regime.[12]

Overall, the dictatorial regime has turned Eritrea into a lawless nation of prisons and prisoners. It maintains an extensive network of jails and detention camps, including shipping containers and underground dungeons. Reliable reports indicate the existence of about 360 prisons, 47,500 prisoners, over half of whom have become paralysed or disabled by torture or lack of adequate medical care. These are shockingly staggering figures for small Eritrea!

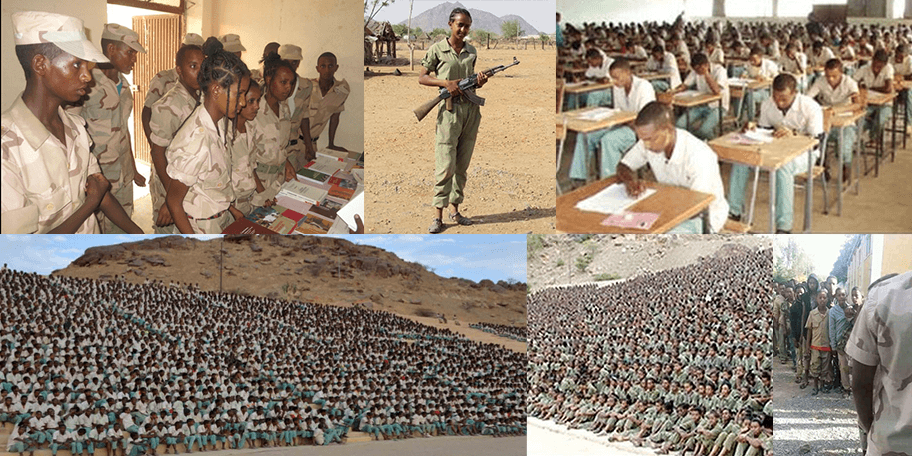

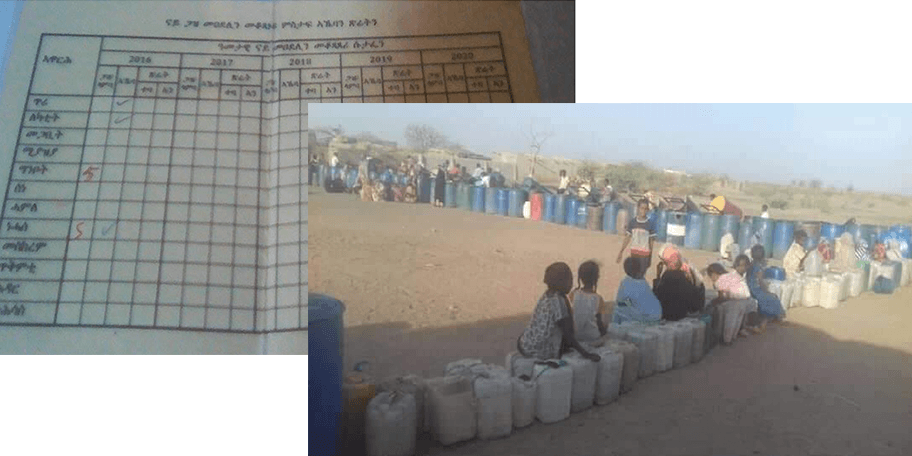

ii. Regimentation of Society and National Service

Mass unemployment is the norm as the regime’s policies and practices have ruined the economy and paralysed the private sector. With their businesses shut down or unable to operate, the professional and entrepreneurial class have fled the country en masse. Mismanagement of the economy and national resources has caused chronic shortage of basic goods and essential services, with the people made dependent on coupon rations for daily subsistence. The regime had used the UN imposed sanctions for years, which were partly self-inflicted by its own incompetence, to externalise blame for the consequences of its own failures, erratic policies and malevolent acts.[13]

The imposition of a coupon economy in peacetime, where even basic rations are affected by chronic shortages, in this 21st century of great agricultural, industrial and technological progress, is a demeaning anomaly that the Eritrean people have been compelled to endure, hardly getting the bare minimum for daily survival. Eritreans at home without family or friends in the Diaspora sending remittances to pay for the rations are left destitute. The general human condition is further aggravated by substandard health services, inadequate facilities, lack of medical supplies and problems of access, especially in the remote areas. In brief, Eritreans are living a bleak reality with no prospects for improvement under the malgovernance of a dysfunctional regime incapable of meeting its obligations and responsibilities towards fulfilling the right to adequate standard of living (ICESCR, Art. 10) and improving the quality of life for Eritreans.

The regimentation of society via the coupon economy, endless national service and multiple layers of constant monitoring and tight control over the daily life of Eritreans constitute elements of a strategy of regime survival. The regime has deliberately perverted the system of national service betraying not only the original purpose of the programme, which was intended to serve as a reserve army for deterrence à la Switzerland and help reconstruct infrastructure, kick-start economic development and nation-building following the devastation of a thirty-year war of independence, but also in exceeding the maximum duration of 18 months stipulated in Proclamation 82/1995; to an essentially indefinite nature with conscripts serving for years or even decades on end.[14]

Denied the choice or option of further education and the pursuit of gainful employment, high school graduates are forcibly recruited straight into the national service. The regime claims that its ‘national military service has been misrepresented and misunderstood’, and that it is providing a ‘new generation of young people with equality in education’.[15] It claims that the placement of all 12th grade students at the Sawa military camp ‘creates a level playing field that ensures higher meritorious competition’.[16] It further claims that this policy choice is ‘cogent’ and that the approach consolidates ‘harmony and social cohesion for the new generation’. However, this system of recruitment and transfer of the youth to Sawa, often entails the forced removal of minors under 18 years old from the care of their family through constant rounding ups (ግፋ).[17] Accounts of harsh conditions and punishments, lack of resources and adequate nutrition, poor sanitation and accommodation facilitates reveal a different picture.

Consequently, grades below Grade 12 experience high rates of repetition and drop-out as students seek to avoid the harsh state of ill-treatment, military discipline and poor living conditions in the so-called Warsay Yikalo School at the Sawa military camp. The placement of the students at the Sawa military camp and the militarisation of education avail the regime complete control over the youth to sap their dynamic energy, appetite for learning and aspirations for a better life. Reports of gender-based violence, sexual exploitation and harassment of female students and recruits abound. High drop-out rates for early marriages and children are therefore prevalent amongst girls to avoid the fate of Sawa and national service.[18] This bears long-term negative consequences on women’s education and empowerment. Moreover, the closure of the only university in the country leaves no prospects for meaningful tertiary education or gainful employment after high school, spurring high rates of dropout and driving the youth to flee the county in droves.

Teachers have also been fleeing the country in large numbers due to poor remuneration, harsh conditions and lack of professional choice. National service recruits, with no training or say in the matter are assigned to teaching positions as replacements, lowering the standard of education. The regime therefore does not avail ‘quality education’ and the right to free education guided by four essential criteria as required under Article 12 of the ICESCR: availability, accessibility, acceptability, and adaptability. The lack of investment in the youth as a matter of deliberate policy denies quality education and skills training in key sectors, such as science, technology, agriculture, and industry essential to drive Eritrea towards sustainable development and prosperity.

After completing high school in Sawa, national service recruits are deployed to work across the country in all sectors, including the civil service, schools, hospitals, public works, mining and Front parastatals. They toil in forced labour under harsh working conditions, poor living and sanitary facilities and inadequate food and water supplies. All this, despite the regime’s obligation, in the context of the national service system, to provide them an adequate standard of living (ICESCR, Art. 11), including adequate standards of food, housing, and healthcare.[19] Their meagre remuneration is insufficient to cover the basic cost of living. The case brought against Nevsun, a Canadian mining company, is one example of the regime’s practice of using conscripts as cheap, forced labour to work in gold and potash mines operated by foreign companies.[20] Many recruits also work in parastatals controlled by a few high-ranking members of the regime. The perverted practice of national service currently in place violates the freedom from slavery and servitude (including ‘forced or compulsory labour’ of Eritreans (ICCPR, Art. 8)[21], the right to just and safe working conditions, fair wages, equal opportunities for promotion, paid holidays and reasonable limitation of working hours (ICESCR, Art. 7), and right to family life (ICESCR, Art. 10).

The regime restricts freedom of movement within Eritrea without prior permission under the pretext of national security concerns. In reality, this is intended to reinforce strict population control and impede opportunities for information sharing and communication. Furthermore, the dispersal of national service recruits throughout the country, limiting home leave and allowing little or no chance for mobile interaction are designed to weaken familial and social networks. Such restriction of movement enforced in the country is in contravention of the Eritrean Constitution which gives ‘[e]very citizen shall have the right to move freely throughout Eritrea or reside and settle in any part thereof’ (Art. 19(8)) and the freedom of movement and choice of residence for lawful residents (ICCPR, Art. 12).

3. The Pervasive Impact of Human Rights Violations in Eritrea

The authoritarian regime has refused to implement the ratified Constitution of Eritrea, suspended the National Assembly, postponed national elections indefinitely, and banned political parties and autonomous civil society associations. The virtually defunct ruling People’s Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ) is the sole political organisation allowed to exist and operate in the country. The regime has claimed that “formation of political parties has been deferred pending the enactment of relevant laws”.[22] It has, however, neither shown any indication nor taken any step to this effect. This fact is unlikely to change given that the regime pursues only policies and actions that ensure the continuity of its own rule. Moreover, in refusing to hold elections, the regime is violating the right of Eritrean’s to exercise their freedom of opinion and expression (ICCPR, Art. 19). In a similar vein, Eritreans are denied their right of peaceful assembly (ICCPR, Art. 21). Holding peaceful public meetings and demonstrations is fundamental to democratic societies and integral to the fundamental rights of freedom of opinion and expression.

Eritreans are capable of making decisions and undertaking action in pursuit of their aspirations, wishes and desires. They have demonstrated this capacity in the extraordinary commitment and persistence that enabled them to win the war of national liberation against overwhelming odds. The system of ruthless suppression and harsh punishment of the Eritrean people for wanting to exercise their basic human rights and express their wishes and aspirations is unacceptable. The regime has been engaged in spinning a false narrative and fabricating flimsy excuses. Worse still, its claim that the people are not ready to exercise their democratic right to vote is, to say the least, quite condescending and an insult to their intelligence and wisdom. The repressive regime, which has neither consulted the people nor received their mandate to rule, cannot correctly judge their competence or claim to know their needs, wishes and aspirations.

Victims of the regime’s gross, systematic and widespread violations of human rights and brutal practices, including national service recruits trapped in an endless system akin to modern servitude, have been fleeing the country en masse. Objectively, the perverted implementation of the programme of national service has proven counterproductive to the very development it was designed to bring about. General mismanagement, coupled with the mass flight of skilled and able-bodied citizens in their prime years, has fuelled the steady decline of the national economy, the overall regression of the country and the disruption of the very fabric of society. Eritrea has also forfeited potential investment opportunities to support genuine nation-building and sustainable development due to years of self-inflicted international isolation and forced emphasis on a distorted form of self-reliance.[23] The regime has been squandering Eritrea’s opportunities for economic development and growth and driving the youth, its most valuable resource, to flee. Denied freedom of expression and freedom of choice at home, the Eritrean people have voted and continue to vote the only way they can - with their feet.

The apparent rapprochement with Ethiopia and the signing of the Joint Declaration of Peace and Friendship a year ago have been used to portray a seemingly reconciled and resolved situation. As stated in previous commentaries, however, Eri-Platform reiterates, once again, that the boundary issue, the ostensible cause and trigger of the border war, remains unresolved and that there exists no institutional framework to sustain and consolidate the ‘new’ relations between the two countries towards genuine and viable peace.[24] In the absence of institutionalised state-to-state relations, the present person-to-person relations, subject as they are to the whims and interests of the respective leaders, bear a high risk of repeating the history of the 1990s between the two states. The Eritrean regime’s connivance to forgo consolidating a viable relationship based on durable peace by addressing the underlying issues that have caused the people and the State of Eritrea so much suffering and distress for decades exposes its contempt of and disregard for the genuine well-being and prosperity of the Eritrean people.

The apparent rapprochement between the two countries and subsequent moves towards improved overall relations in the Horn of Africa region have raised expectations of political and institutional reforms in Eritrea among the Eritrean people and the international community. Contrary to these expectations, the regime has neither changed its dictatorial methods and repressive practices nor given any hint, indication or plan to do so. Lack of positive steps following the removal of the two pretexts clearly reaffirms the regime’s primary preoccupation with the sole pursuit of its own self-preservation. Given its appalling human rights record, its seeming re-engagement with the international community, starting with its membership in the UN Human Rights Council, is but a shameless attempt to impede scrutiny of its abysmal violations. Hence, the Human Rights Council Resolution A/HRC/41/L.15 adopted on 7 July 2019, extending the mandate of Daniela Kravetz, Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Eritrea for one year and requesting the Office High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) to present an oral update to the 43rd Human Rights Council in March 2020.

4. The Imperative for Restorative Justice in a New Eritrea

There will be an imperative need to address the scale and magnitude of the human rights violations and abuses perpetrated against the Eritrean people for so long. Ensuring justice for the victims and accountability for the perpetrators of the gross, systematic and widespread violations of human rights would be essential for national reconciliation and indispensable for successful transition to democracy, peace and prosperity in Eritrea. The challenges of applying restorative justice in a new Eritrea will be predicated on rebuilding key institutions and establishing effective mechanisms of oversight and accountability. This must start with the immediate implementation of the ratified Constitution of Eritrea, setting up an independent judiciary and instituting democratic governance with the active and full participation of the entire Eritrean people.

In essence, restorative justice seeks to (1) repair the damage caused by crime(s) committed (3) find closure for the victims; (3) engage the victims, the offenders, and the community, respectively to, (4) deliver a sense of justice, encourage the taking of responsibility, and promote communal engagement for reintegration and cohesion. The ultimate objective is to foster a sense peace and coexistence capable of preventing or minimising the possibility of recurrence.

Given the protracted nature and shared trauma experienced under the authoritarian regime, we Eritreans need to find a way to put aside our differences and historical baggage, engage in open dialogue and cooperate more effectively to sustain common action. As such, we need to urgently begin to take ownership of our situation and seize our future by building bridges and reconnecting as a community based on a common understanding and shared vision for a new Eritrea.

______________________

[1] The ICCPR and ICESCR include: (1) Optional Protocol International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights: First Option Protocol (23 March 1976) and Second Optional Protocol (15 December 1989) and (2) Optional Protocol International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights,10 December 2008.

[5] ‘Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action’. Adopted by the World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna on 25.06.1993

[6] ICCPR Art. 4(1)

[8] CCPR/C/GC/34: Paragraphs 11 and 12.

[9] CCPR/C/GC/36: paragraph 57 and 58.

[10] A/HRC/32/CRP.1: Paragraph 263.

[11] A/HRC/41/53.

[12] For example: (1) Abune Antonios, Patriarch of the Eritrean Orthodox church, who is over 90 years old, has been under house arrest since 2007 after calling for the release of priests, and calling out the regime’s interference in the church. (2) Chairman of Al Diaa Islamic School, Haji Musa Mohamednur, 93 years old was detained in October 2017 and died in custody in March 2018.

[13] The UN Sanctions were an arms embargo and not economic sanction, nor targeted any Eritrean individuals

See: Eri-Platform (May 2018). ‘The Case for Lifting Sanctions on Eritrea’ (link); and

Eri-Platform (November 2018). ‘Lifting sanctions removes a useful tool for the Eritrean regime’ (link).

[14] It must be noted that several countries, including Greece, Israel, Egypt, Switzerland, have mandatory national service that respects the legal duration and serves a constructive purpose. Compulsory national or military service systems allow citizens to pursue further education and fulfil family goals while fulfilling their national duties, thereby ensuring that they are able to find gainful employment, grow a family, and contribute to the development of the country upon completion of their service. In this regard, the UN Commission of Inquiry report states that ‘compulsory military or national service is, in and of itself, neither a human rights violation nor a crime against humanity, provided it is regulated, uniform, and proportionate to the needs of the state.’ What is unacceptable and unjustifiable is the manner of implementation of Eritrea’s national service system.

[15] A/HRC/41/53, p. 7.

[16] A/HRC/WG.6/32/ERI/1: Paragraph 66.

[17] Human Rights Watch, (2019). Report: “They Are Making Us Into Slaves, Not Educating Us”. (Excerpt), p. 79:

“Eritrea has ratified the Optional Protocol of the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict (the “Optional Protocol”), which prohibits any forced recruitment or conscription of children under 18 by government forces, and the participation of children under 18 in active hostilities. Under the Optional Protocol, while the recruitment of children aged 15 to 18 is permitted, recruitment should be genuinely voluntary and carried with the informed consent of the child’s parents or guardians.”

[18] Ibid.,

[19] A/HRC/29/CRP: Paragraph 1183.

[20] Amnesty International (Canada), (2019). ‘Canadian company before Supreme Court of Canada in major corporate accountability case’ (link).

[21] In addition to the ICCPR Article 8 prohibiting forced and compulsory labour, the International Labour Organization (ILO) Forced Labour Convention, 1930 (No. 29), and the ILO Abolition of Forced Labour Convention, 1957.

[22] A/HRC/32/CPR.1: Paragraph 141

[23]Andebrhan Welde Giorgis, (2014). Eritrea at a Crossroads: A Narrative of Triumph, Betrayal, and Hope. See Chapter 7.

[24] Eri-Platform,

(2019). ‘Commentary - Securing Viable Peace between Eritrea and Ethiopia’.